Why is this cat with a huge left atrium not in congestive failure?

This is a cat we saw last week. She presented for routine vaccination and was found to have a tachydysrhythmia. No hyperpnoea, no dyspnoea, outwardly well.

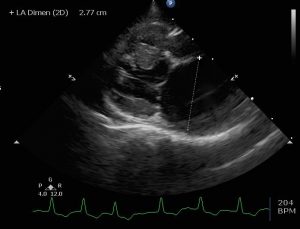

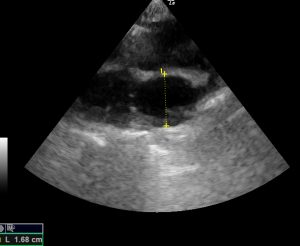

This is her echocardiography. First, right long axis four chamber view:

Her left atrium measures about 28mm (normal being <16mm). Technically, that falls into the ‘huge’ category.

Right long-axis four-chamber view

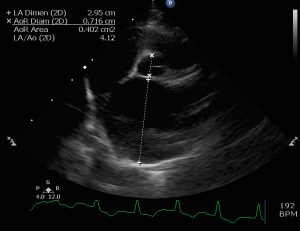

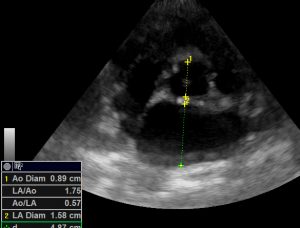

Right short-axis view of left atrium and aorta

She has atrial fibrillation. We’ll leave aside the possible causes of these changes (it would be a long blog). Really, I’m interested in why she remains outwardly well. Most of the cats we see with left-sided congestive failure start to exhibit pulmonary oedema or pleural effusion once the left atrium reaches about 20mm (pre-diuresis). Surely, at 28mm she must be in CHF?

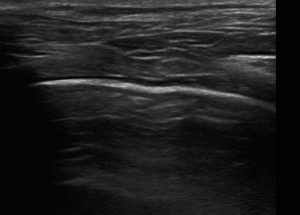

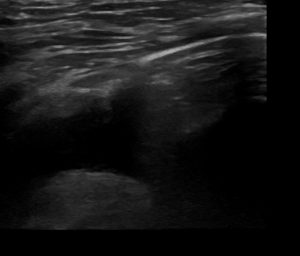

Well, not only is her respiratory rate within normal limits, her lungs look fine too:

Transthoracic lung ultrasound: normal A lines, no B lines

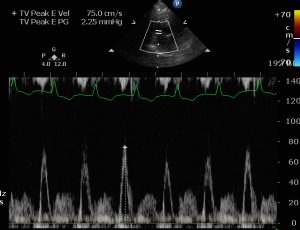

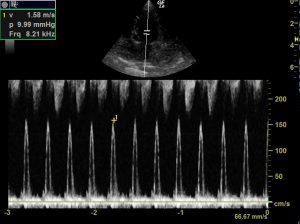

It’s interesting that her transmitral flow velocity is within normal limits:

In contrast, we have a second cat also from last week. This patient presented with acute onset tachypnoea, hyperpnoea, hypothermia, murmur and gallop.

And still images:

Right long-axis four-chamber view

right short-axis left atrium aorta view

She has an anechoic pleural effusion:

transthoracic view of lung and pleural effusion

Again, for the purposes of brevity, I am going to summarise that she has no other obvious cause for the pleural effusion other than left sided CHF. The pleural transudate proved to be frusemide-responsive and she has markedly supranormal transmitral flow velocity.

But the obvious debating point is that this cat has a relatively normal left atrial diameter. And she hasn’t had any diuretics at this point! What is the difference between these cats? What are the implications for diagnosis of L CHF?

The key is likely to be left atrial compliance.

The driving force for pulmonary oedema and pleural effusion is left atrial and pulmonary venous pressure. But high pressure isn’t necessarily reflected in increased LA size: this is also governed by wall compliance.

Postepy Kardiol Interwencyjnej. 2018; 14(2): 120–127.

Left atrial compliance: an overlooked predictor of clinical outcome in patients with mitral stenosis or atrial fibrillation undergoing invasive management

Joanna B. Hrabia,1 Elahn P.L. Pogue,1 Alexander G. Zayachkowski,1 Dorota Długosz,1 Olga Kruszelnicka,2 Andrzej Surdacki,3 and Bernadeta Chyrchel

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6041835/

At different stages of the cardiac cycle the left atrium fulfils different functions.

- ventricular systole: reservoir

- early diastole: conduit

- late diastole: pump

Reservoir function depends on distensibility or compliance. In states of reduced left atrial wall compliance pressure builds rapidly. Accentuated compliance provides a buffer against elevated pressure.

So far, so good in theory. What do we know about what kind of LA wall changes increase or decrease compliance? The answer to this seems to be not a whole lot in cats and dogs.

In human medicine there is an interesting syndrome of ‘giant left atrium’ (GLA):

The surgical management of giant left atrium

Efstratios Apostolakis Jeffrey H. Shuhaiber

European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery, Volume 33, Issue 2, 1 February 2008, Pages 182–190

https://academic.oup.com/ejcts/article/33/2/182/404878

GLA is the archetypal scenario of massive left atrial dilation without L CHF. The commonest cause is rheumatic heart disease: cardiac inflammation and scarring triggered by an autoimmune reaction to infection with group A streptococci. Although aetiology remains a matter of some debate, two factors seem to be important:

- long term, chronic mitral regurgitation

- left atrial fibrosis and inflammation

Conversely, the commonest cause of reduced LA compliance appears to be primary (but, interestingly, not secondary) hypertrophic cardiomyopathy:

Dardas PS, Fillippatos GS, Tsikaderis DD, Michalis LK, Goudevenos IA, Sideris DA, Shapiro LM

Noninvasive indexes of left atrial diastolic function in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2000; 13: 809–17

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10980083

These authors conclude that HCM is not confined to ventricular myocardium: atrial wall relaxation is a potentially important factor.

If the same is true for cats then it seems possible that the primary pathology in the large-atriumed patient might be something like a chronic myocarditis (e.g. FIV) and perhaps our small-atriumed CHF cat has primary HCM.

That’s speculation. The important take home message is that LA size alone can’t be assumed to be a reliable indicator of the presence/absence of CHF. Transmitral and pulmonary venous flow profiling can help sort out what’s going on in difficult cases.