Ureteral obstruction in cats

It’s been an interesting few weeks of nephrology for ultrasound4pets.

Ureteral obstruction in a cat was first described in 1990. From there we have now moved to a situation where it has been described as ‘the leading cause of acute uraemia in North American cats’. The evolution of understanding has accelerated dramatically in the last few years and is now covered by quite an extensive literature.

Take this patient -a young neutered male cat with a history of occasional anorexia with vomiting. Now presented with just such an episode, moderate azotaemia and a right-side nephrolith on radiography.

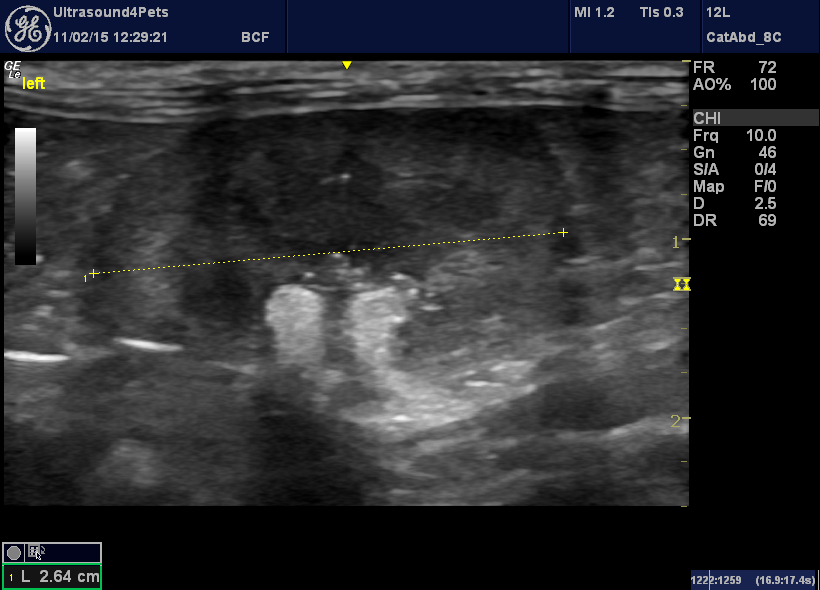

On ultrasonography, the left kidney:

This is a small kidney (2.8cm) without dramatic pelvic dilation but exhibiting mineral deposition in/around the pelvis.

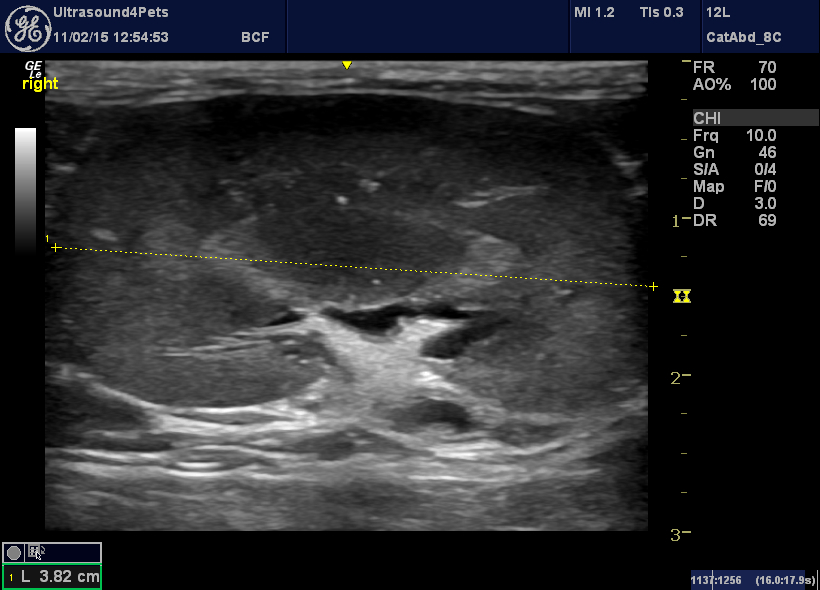

The right kidney:

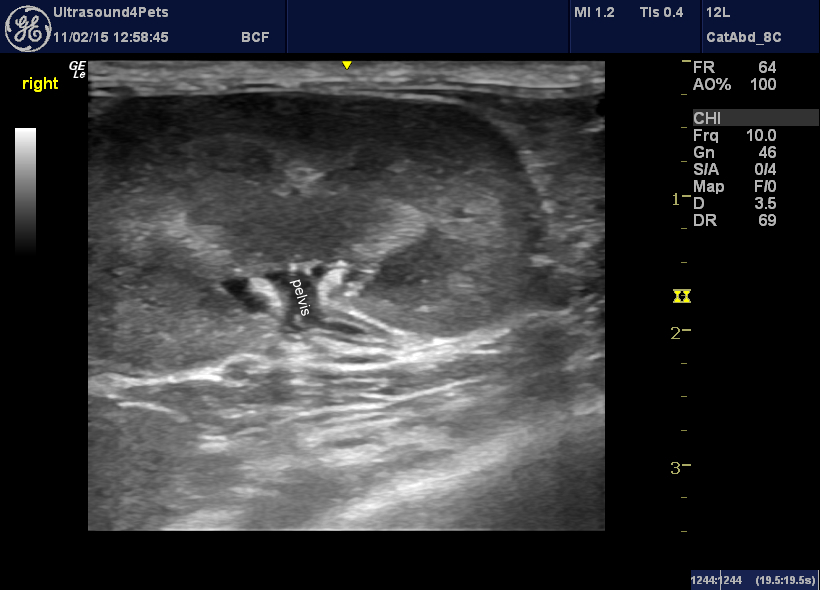

…is much larger -in fact close to the middle of the normal range. The renal pelvis is visible and was measured at 4mm on transverse views. Larger than average but not dramatic. Again there is considerable mineralisation around the hilum.

In this view the proximal ureter is visible and appears dilated (normal lumenal diameter is @0.4mm) with an abnormally thickened wall.

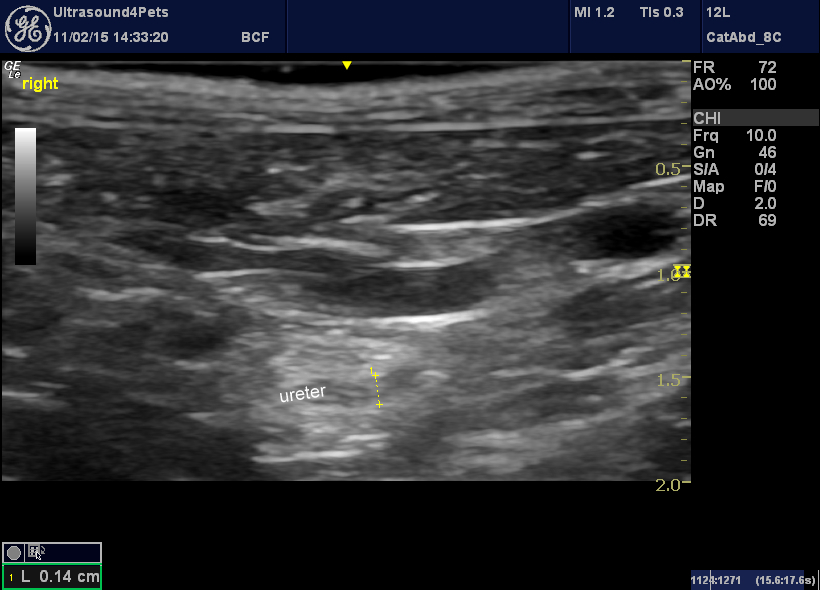

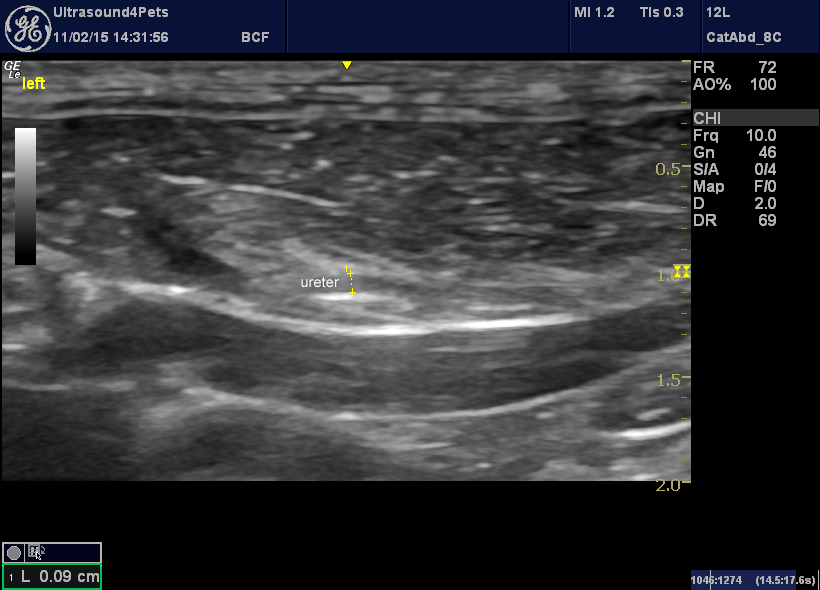

The middle section of the ureters are also somewhat dilated on both sides:

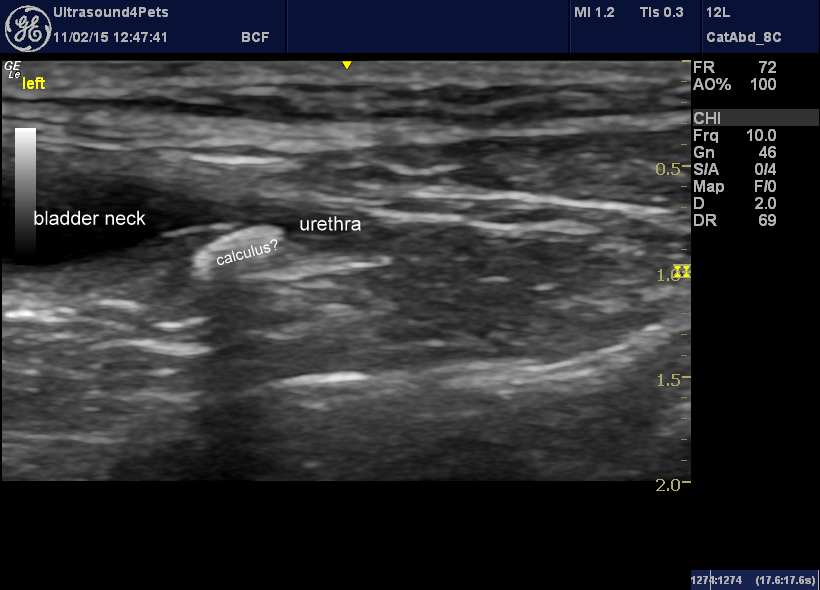

And at the bladder trigone there is what appears to be a ureteral calculus in one of the ureters close to its termination.

So, what’s going on here? We have a ‘big-kidney-little-kidney’ scenario. It is likely that the small, left kidney has suffered a previous episode of ureteral obstruction which has left it with reduced mass and function. The contralateral, right kidney may undergo compensatory hypertrophy.

Although the lateralisation of the ureteral calculus at the bladder neck couldn’t be proven at the time it is likely that it is on the right. Urea and creatinine levels (assuming euhydration) reflect the residual function of the left kidney.

The interesting thing is the lack of dramatic renal pelvic or ureteral dilation. In a landmark paper in Veterinary Radiology & Ultrasound in 2011 Marc-Andre D’Anjou and others showed that, contrary to what had previously been believed, dilation of the collecting system proximal to obstruction may be inconsistent and/or take several days to develop.

These cases are a real challenge in several respects. For decision-making in this cat we need to know the degree of patency of both ureters. This is going to require a combination of imaging modalities. Since renal perfusion is probably compromised intravenous urography may not help. We could perform ultrasound-guided injection of radiographic contrast into the renal pelvices -but this would be a lot easier if they were dilated. Or, contrast can be introduced retrograde at surgery or via cystoscopy.

It is possible that the visible ureteral calculus may pass into the bladder -it is close to the termination of the ureter. Diuresis may encourage the process. Subsequent renal function is well-preserved so long as the calculus passes within a few days. Beyond a week renal function is likely to suffer permanent impairment.

If it doesn’t pass soon then the options are surgery (ureterotomy or resection and re-implantation -but these are technically challenging in cats and are associated with really significant risk of serious complications and a high recurrence rate) or minimally-invasive management with endoscopic stent placement. This probably represents the best option but requires a lot of very specialised care. We cannot be sure that we can see all ureteral calculi in this case -the detection rate with ultrasonography is certainly well below 100% no matter who does the scan. Multiple calculi are probably quite common and represent a clear reason to opt for stenting rather than surgery.

…..there’s more but it’ll have to wait for now.