Should we recommend CT angiography for all potential portosystemic shunts -or is ultrasound good enough? Part I: extra-hepatic shunts

In all images here cranial is to left of image.

I’ve listened to two authoritative presentations on shunts by specialist surgeons in the last month. To paraphrase, both of them said they recommend CT angio and find ultrasound too user-dependent and too unreliable. My impression is that there’s a general drift in this direction. I suspect that CT is now the default imaging modality for ‘shunt hunts’ in all almost UK referral centres.

My concern is that this adds a significant amount to the cost and also to owner inconvenience: we don’t really know how many owners may be deterred from treatment because of this. Generally speaking, I think it’s important that we balance the narrative that ‘it’s important we offer gold standard treatment’ with the alternative that ‘there are other options and in many cases these other options will work out just fine’. I find it frustrating to see owners quoted £7,000 plus for CT plus surgery when many shunts can be sorted relatively simply with ultrasound and in-house surgery.

The more CT angiography becomes the default, the less imagers get the chance to gain experience of shunt sonography. For me, that’s a pity. I think most texts somewhat over-complicate the matter: our experience as a team of sonographers is that the vast majority of shunts can be diagnosed and described once portal vein anatomy is conceptualised and some practical tricks are applied. The default to CT can become defensive medicine unless sonographers have the confidence to make a call one way or the other.

A further issue (my colleague Hazel reminds me!) is the large doses of radiation administered to young animals during CT angiography for shunt hunts. The risk engendered is hard to quantify but remains a matter of concern and ongoing research.

A shunt hunt protocol

Circumstantial evidence…. big kidneys, small liver, crystalluria, portal vein to aorta ratio…these things are useful. But, at the end of the day, we want to know for sure how flow in the portal circulation is directed. I don’t measure PV:Ao (ratio of diameter of portal vein to diameter of aorta) any more. It’s insufficiently reliable: especially in dogs with phrenic or azygos vein shunts.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1090023313005698

For one thing, in patients with raised bile acids, even young animals (e.g. those with ductal plate malformation), there’s always the possibility of multiple acquired shunts and those patients have large portal veins.

Extra-hepatic shunts (EHPSS):

In most cases, 3 views are going to give you the information you need.

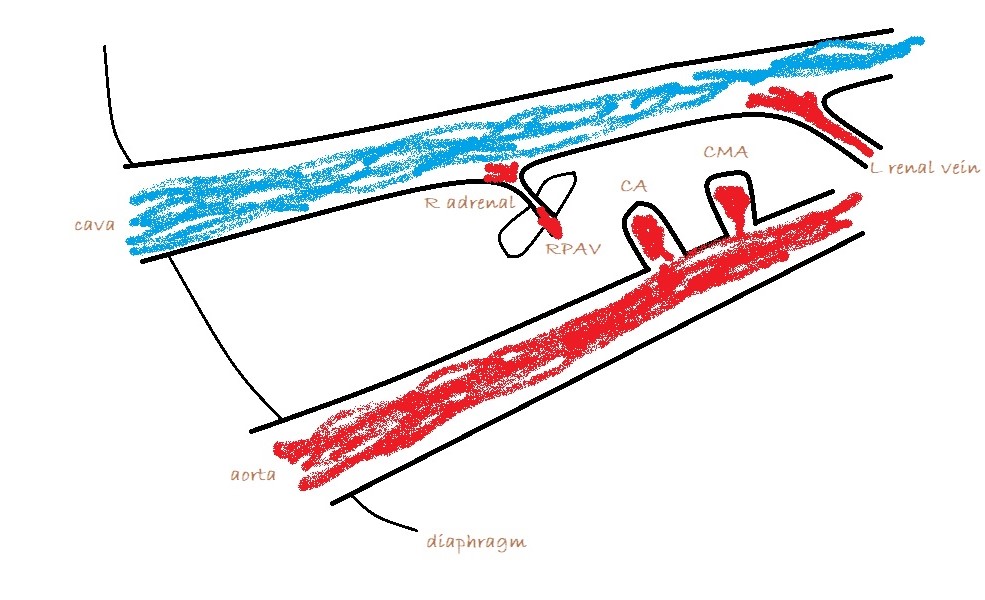

1: Long axis, R sided view from immediately caudal to the last rib directed cranio-dorsally to see the major vessels. The cava and aorta should be readily visible.

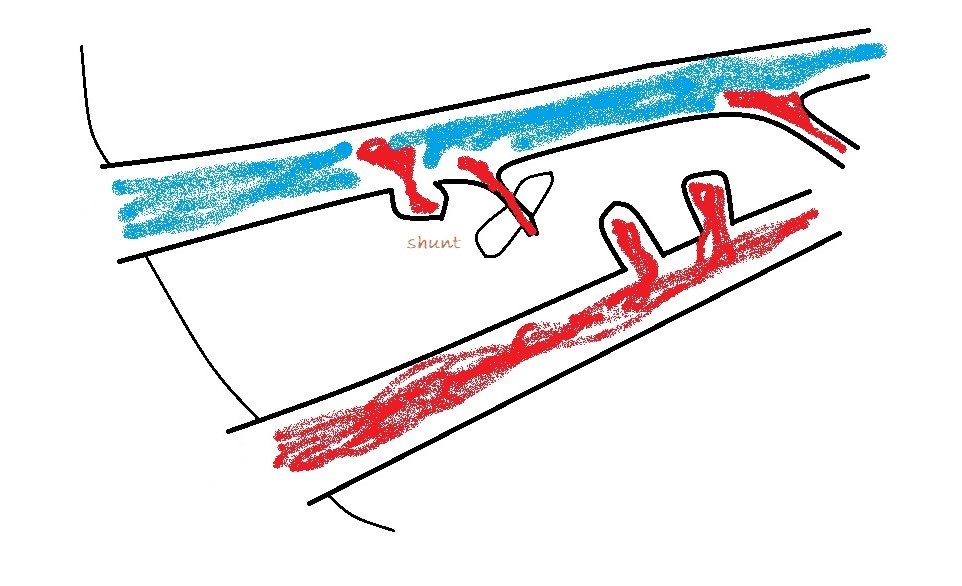

Apply colour Doppler and look for large vessels between cava and aorta. There shouldn’t normally be any. The vast majority of extra-hepatic shunts are running in this area to one of three destinations:

a) The cava at the level of the omental foramen (just cranial to origin of the coeliac artery from the aorta)

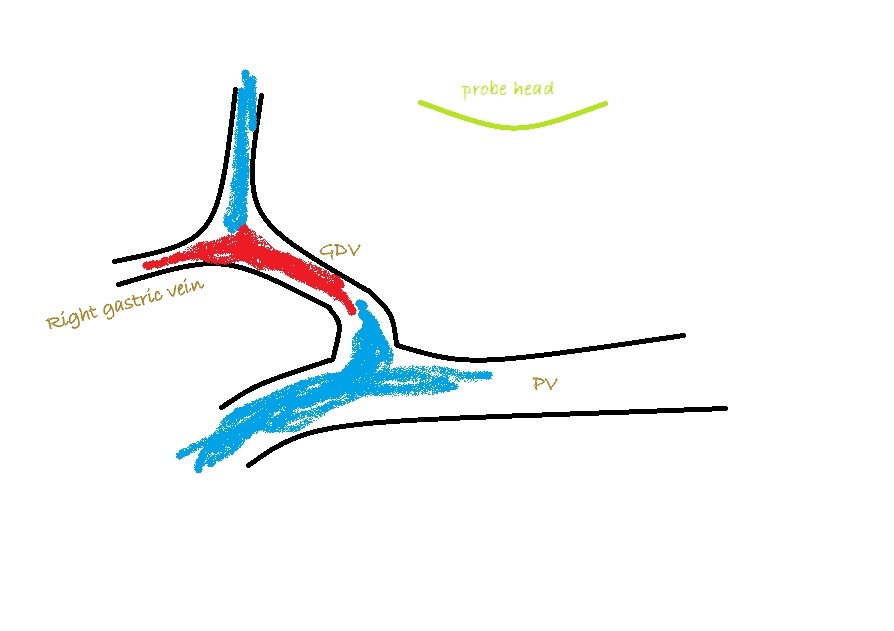

A bit of turbulence in the cava can be over-interpreted. However, a jet which is directed across the cava perpendicular to its long axis and is located at the omental foramen is highly suspicious. In this case, turning off the the colour and zooming in you should be able to see an abnormal vessel entering the cava cranial to the phrenico-abdominal vein (which crosses the right adrenal).

b) azygos vein: obviously alongside the aorta

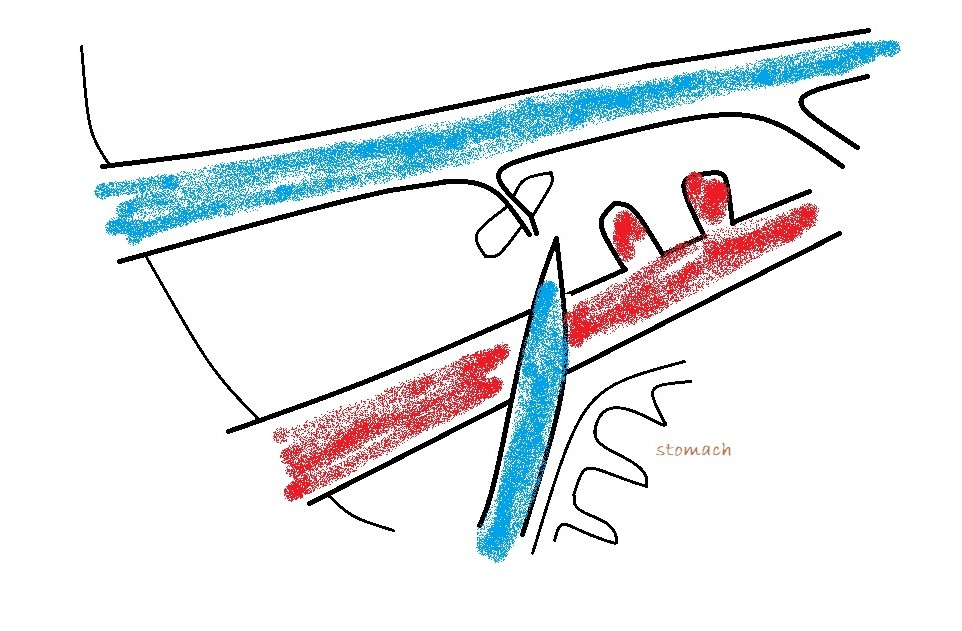

c) left phrenic vein: in which case the vessel will be running away from the probe to the left as it curves around the lesser curvature of the stomach.

From a surgeon’s point of view the destination of an EHPSS is the important thing. To a large extent, it’s academic where it’s coming from. Congenital shunts to the cava almost always enter from the left at the level of the omental foramen and are accessed through the foramen with the duodenum reflected to the left. Congenital shunts to the azygos take a route close to the midline and often need to be accessed via a surgical opening in the omentum. Left phrenic vein shunts may run on the left or on the right aspect of the oesophagus: the relation to the oesophagus is important to know in advance. Those on the left are generally very easy to find at laparotomy. Those on the right of the oesophagus may be hidden by omentum and diaphragmatic crura: it’s nice to know that they’re in there before you start bluntly dissecting.

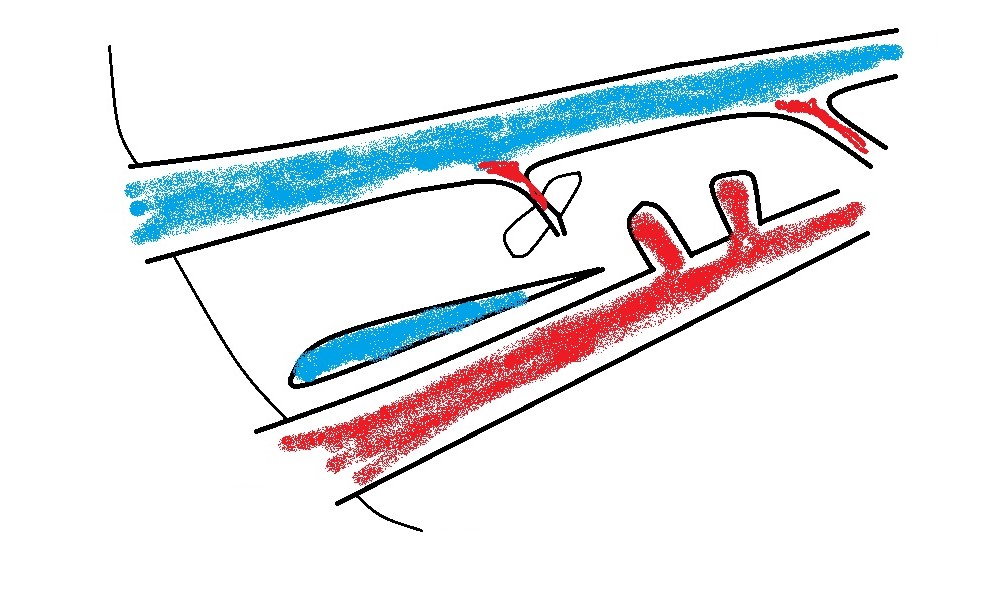

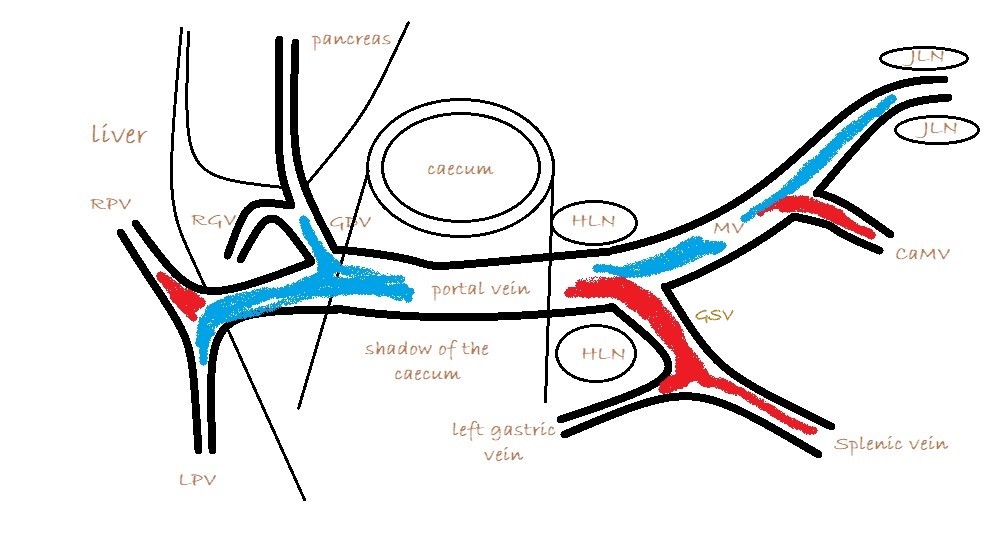

2: From the view described above, fan ventrally to find the main portal vein (PV). The only large vessels visible ventral to the cava under normal circumstances are either the portal vein or (further caudal) the mesenteric vein which runs into the PV. This where a bit of technical jiggery-pokery is required. The PV is often shadowed by gas in the caecum. But this can almost always be persuaded to disperse with gentle manipulation with the probe head. Often it’s possible to see the caudal end of the portal vein with a particular manouevre and then a separate effort is required to see the cranial part. Sedation greatly facilitates this in many patients. In tense or large dogs it really takes quite a lot of sustained pressure sometimes to get the probe close to the vessels and to push everything else out of the way. As an aside, it’s often stated that an empty stomach is necessary for shunt hunting: but, as you’ll see from the images, the stomach shouldn’t impact on these views regardless of its content.

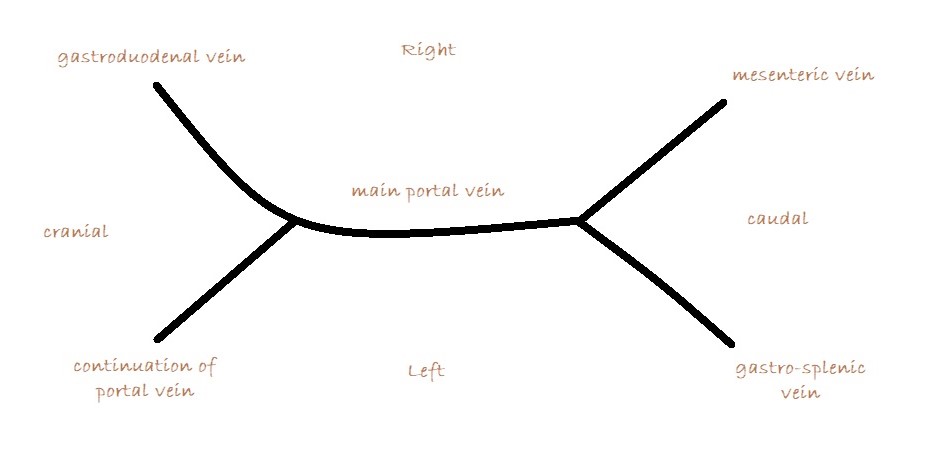

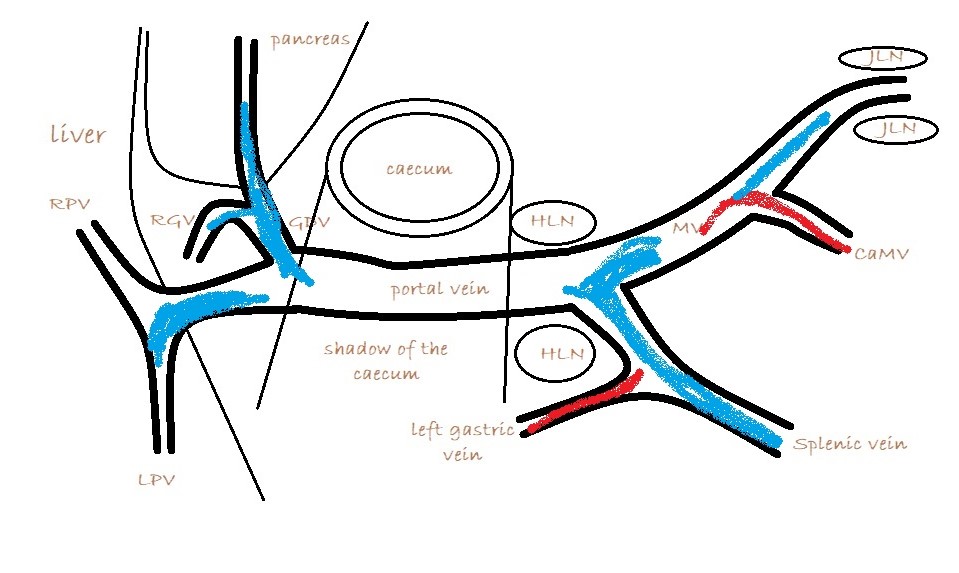

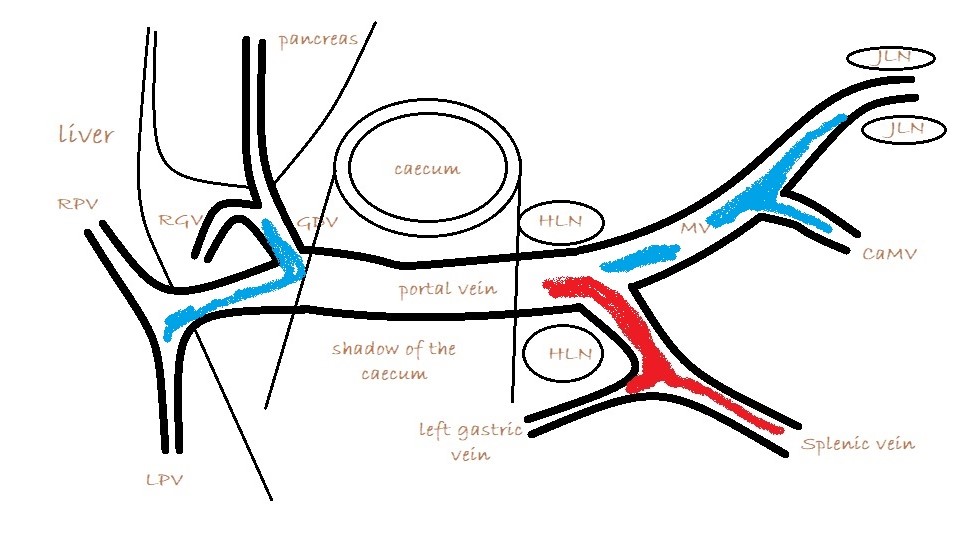

What you are looking for is a longitudinal plane view of the main PV with its caudal tributaries the mesenteric and gastro-splenic veins coming together to form the PV. A few cm cranial to this the gastro-duodenal vein joins as a further tributary from the right side; only a cm or two before the PV enters the liver. Identification of these vessels can be confirmed by following the mesenteric vein caudally to the point where it runs between the large jejunal nodes and by following the gastro-duodenal vein back into the body of the pancreas caudal to the cranial duodenal flexure (in reverse this can be a useful way to locate the pancreas). Hepatic nodes sit either side of the main portal vein at the confluence of mesenteric and gastro-splenic veins.

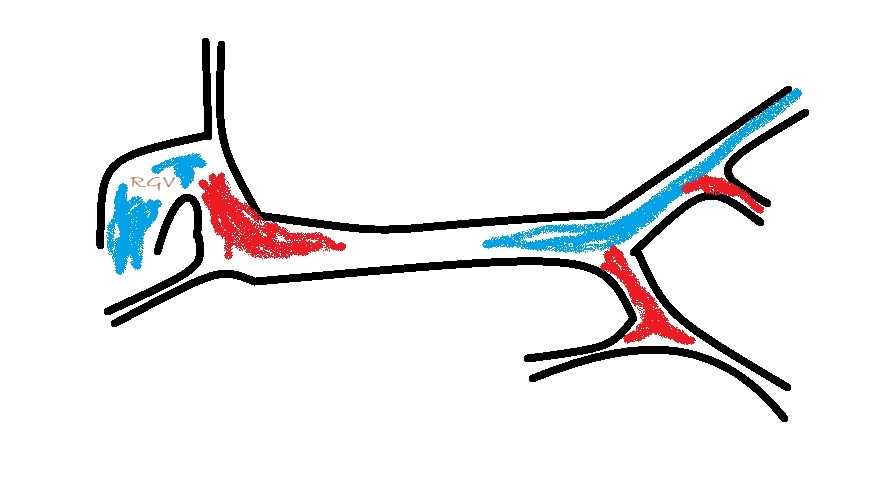

This arrangement of vessels, as seen from the right in longitudinal plane, has the appearance of an ‘envelope’. Fig

As seen from the right with colour Doppler, flow in the gastro-splenic and caudal mesenteric veins should be hepatopetal and red coded. Flow in the gastro-duodenal should be hepatopetal and blue coded at the point of entry to the portal vein. Due to angulation of view, the gastroduodenal vein may be flowing towards the probe as it approaches the PV (and thus red coded) but flow into the PV at the junction will be running away from the probe (blue) under normal anatomy.

It’s important also to look at flow in the caudal mesenteric vein which unites with the cranial mesenteric vein caudal to the entry of the gastro-splenic vein. In animals with colic vein shunts or with multiple acquired shunts, flow in the caudal mesenteric vein may be hepatofugal (blue coded as seen from right) and this may be the only abnormality of flow direction in this standard right-sided view of the portal vein and its tributaries.

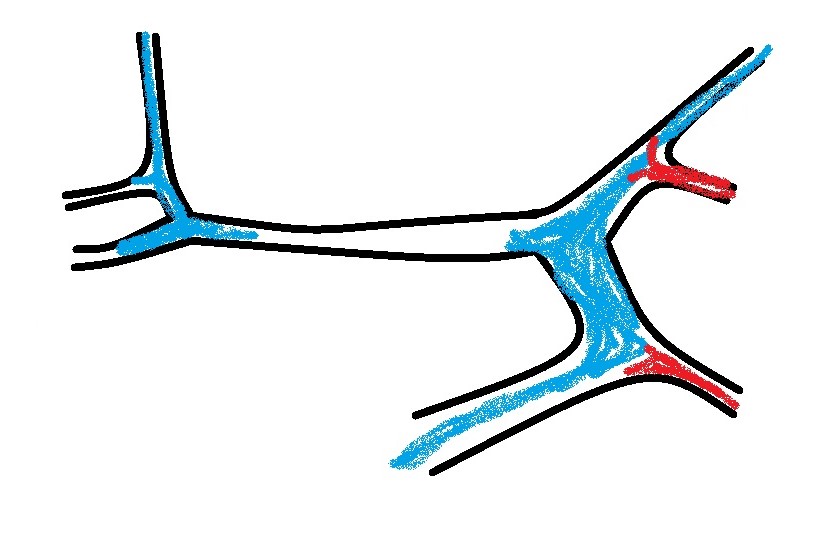

Appearance of the portal vasculature with EHPSS:

Veins are enormously responsive to pressure and will expand or contract (passively) depending on circumstances. Where there is a congenital EHPSS, the normal pathway which is deprived of flow may be very small. This can distort the overall appearance of the portal vasculature -making it a challenge at first glance, to work out what the hell is what. Under these circumstances it’s necessary to use the reference points of lymph nodes and pancreas to identify each vessel. Occasionally, the portal vein may be imperforate: with no continuation to the liver. This is important to recognise (those ones aren’t surgical candidates!). It may take careful inspection to identify flow in a very small portal vein continuation…even if they’re <1mm diameter they can usually accommodate flow after attenuation of the shunt. However, the risk of developing subsequent acquired shunts is probably increased.

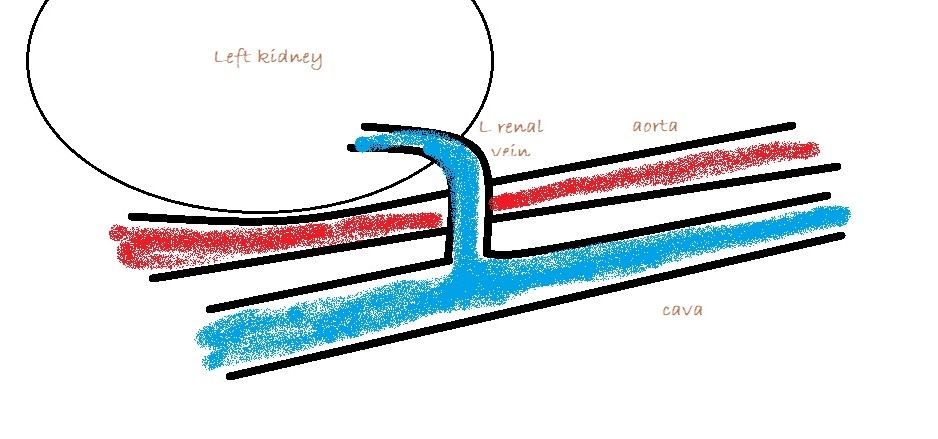

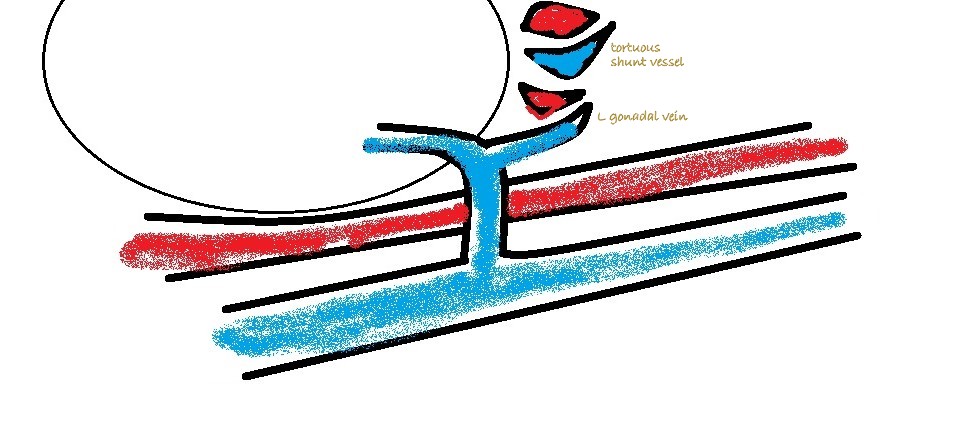

3: Left sided longitudinal plane view of the cava and left renal vein. Essentially you are looking for abnormal vessels entering the renal vein on its caudal aspect (there should be none).

Congenital splenic-to-left renal shunts are not uncommon in female cats. Shunting to the left renal vein is the most consistent termination of MAPSS in cats and dogs… or at least the most consistently visible.

MAPSS in the mesocolon and in the area of the PV can be picked up on colour Doppler with practice …but it’s often difficult to be completely certain about their identity in those areas. As mentioned above, patients with MAPSS in the mesocolon almost always have hepatofugal flow in the caudal mesenteric vein.

Brilliant post, far clearer than most textbooks!

Many thanks!

very very helpful!! brilliant post