Putative Canine Toxic Shock Syndrome associated with Staphylococcus pseudintermedius cellulitis: sonographic features and a review of the literature

The patient on this occasion was an 11 y.o. FN Border Collie with a history of a traumatic wound to the right fore paw surgically repaired a couple of months earlier but otherwise in good health. She presented acutely depressed, anorexic and deteriorated to the point of recumbency within 24 hours. Purulent discharge from the previously-injured paw was noted and she was febrile (41C) with tachydysrhythmia and moderate systemic hypotension (some variation in precise readings).

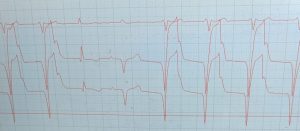

ECG demonstrated sinus rhythm drifting in and out of accelerated idioventricular rhythm (heart rate 165/min)

Principal derangements noted on routine haematology & plasma biochemistry:

Platelets 57 (ref >200 x 10^9/l)

Creatinine 265 (ref 44-160)

Urea 12 (ref 3-9)

albumin 23 (ref 23-40)

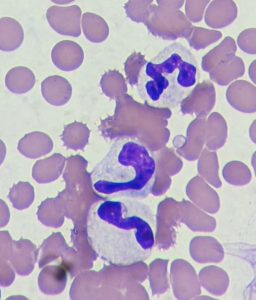

On blood smears toxic neutrophil changes were apparent:

Sonographic changes:

Echocardiography showed a heart with broadly-normal chamber proportions but markedly compromised systolic function and spontaneous echocontrast in the left heart.

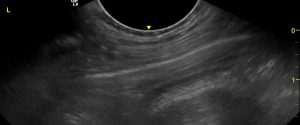

Lungs were unremarkable:

Lung

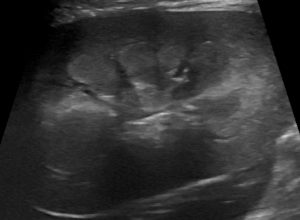

Liver was diffusely hypoechoic but otherwise alesional. In contrast, abdominal fat was diffusely, markedly hyperechoic.

Longitudinal plane view of liver, gallbladder and adjacent abdominal fat

Transverse plane view from the right side showing body of pancreas between cranial duodenal flexure and liver. There were no changes in the pancreas itself to suggest pancreatitis and hyperechoic change in mesentery was not focused on the pancreas.

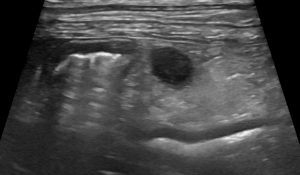

An enlarged, hypoechoic pancreaticoduodenal lymph node

Right kidney, long axis view. There is diffuse, uneven hyperechoic change of the inner cortex.

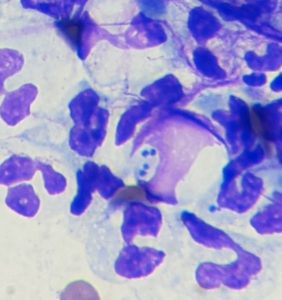

Cytology of exudate from the right fore paw:

Rapid stain cytology preparation from RF paw showing numerous paired intracellular cocci.

Bacterial culture yielded a Staph pseudintermedius sensitive to many antibiotics.

Essentially we have here a syndrome of systemic signs grossly disproportionate to the extent of sepsis. The degree of collapse initially suggested some thoracic or abdominal catastrophe. It was only as further investigation failed to identify any primary internal cause it then became apparent that the pedal infection might actually be relevant to the systemic crisis. Ultimately, it’s always difficult to prove a diagnosis of TSS (especially the distinction from septic shock generally) beyond all doubt: but since she recovered fully with treatment and without evidence of any other primary cause it seems a reasonable proposition here.

Canine toxic shock syndrome (TSS), like it’s human equivalent, has classically been associated with Streptococci.

Can Vet J 1997 Apr;38(4):241-2.

Update on canine streptococcal toxic shock syndrome and necrotizing fasciitis

J F Prescott 1, C W Miller, K A Mathews, J A Yager, L DeWinter

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1576574/

Thus we were somewhat confounded that the cocci seen on cytology weren’t the classic streptococcal chains. However, in human medicine non-streptococcal TSS is well documented:

https://health.mo.gov/living/healthcondiseases/communicable/communicabledisease/cdmanual/pdf/TSS.pdf

Staphylococci and Clostridia are usually implicated. And, indeed, as it turns out, genes coding for TSS toxins have been demonstrated in canine S. pseudintermedius

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31626602/

In Bonnie’s case, aggressive fluid therapy, co-amoxiclav and debridement of the septic foot led to a rapid response within 48 hrs and subsequently to full recovery.

The septic foot after initial debridement

..and at the end of treatment

There is very little published material regarding TSS in dogs and just one report that I can find involving S. pseudintermedius:

https://agris.fao.org/agris-search/search.do?recordID=US201500182918

…although there is one other case from which a coagulase-positive Staph was cultured.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1365-3164.2004.00410_5-7.x