Pulmonary arterial hypertension in a cat with left- and right-sided heart disease but no pulmonary oedema

This is a an adult DSH of unknown age and provenance who presented with ascites. His owner reported him as being otherwise active and well. He was not tachypnoeic or hyperpnoeic (resting respiratory rate in the clinic 26/minute).

ventral view of tummy!

On auscultation he does have left and right-sided murmurs and a gallop sound on the left.

Ultrasonographically, his abdomen is unremarkable except for large volume of ascitic effusion and dilation of the cava and hepatic veins:

longitudinal view of liver and diaphragm

The heart is markedly abnormal:

Subjectively, there is bi-atrial dilation. The right ventricle appears broadly unremarkable (possibly some free wall hypertrophy) but the left ventricle is dilated with a thin-walled and hypocontractile apical part.

Objectively, the left atrium measures a whopping 25mm in long axis at end-systole:

Basal parts of the LV free wall are marginally hypertrophic:

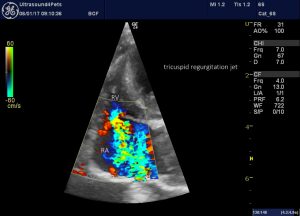

There are jets of mitral and tricuspid regurgitation:

Left apical-ish view optimised for the right heart showing a large central jet of tricuspid regurgitation

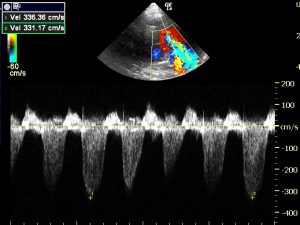

Maximum velocity of the tricuspid regurgitation jet was at least 3.3m/s:

Tipped right long-axis four-chamber view optimised for alignment with tricuspid regurgitation jet and CW Doppler thereof

….indicating a systolic RV pressure of at least

4 x 3.32 = 44 mmHg

Given that there is evidence of right-sided CHF it would be conventional to assume RA pressure of @15mmHg -implying RV pressure (which in systole = pulmonary arterial pressure) of

44 + 15 = 59 mmHg

i.e. convincing pulmonary arterial hypertension.

So far so straightforward. I won’t bore you with the details but a full exam revealed no evidence of any congenital defect -other than the possibility of atrioventricular valve dysplasia which is hard to exclude although valve leaflets were not obviously abnormal on 2D echo. It’s not rocket science to presume that this cat probably has some form of cardiomyopathy with evidence of left and right heart dysfunction. The thin-walled section of LV wall may represent previous infarction. The aetiology is arguably less interesting than the pathophysiology:

Evidence for the presence of right-sided CHF looks pretty convincing. I’m thinking the interesting issues are:

-what is the pathophysiology of PAH in this case?

-if it’s secondary to left-sided CHF then why is there no evidence of pulmonary oedema?

Although the left atrium is very large, the patient is not tachypnoeic or hyperpnoeic. There is no pleural effusion and lung ultrasound is not suggestive of pulmonary oedema.

transthoracic lung ultrasound: lungs exhibit normal array of ‘A lines’ parallel to the pleurae and no ‘B lines’.

OK we don’t have chest radiographs (for financial reasons) and it’s true that there might be pulmonary pathology which we can’t see ultrasonographically. As far as pulmonary oedema goes we have no figures on the relative sensitivity of radiography vs ultrasound: a subject for a future blog. However, in human medicine it is well established that ultrasonography has significantly better sensitivity:

e.g. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4072810/

The $90,000,000 question -is it possible to have PAH secondary to left heart congestive failure (usually classified as group 2 PAH) without pulmonary oedema?

Recent advances in our understanding of group 2 PAH have shown that there’s a lot more going on than just passive transfer of pressure from left to right. To a variable extent and at varying speed, reactive changes in the pulmonary vasculature follow. Pulmonary capillary stress failure, arterial remodelling, endothelial dysfunction and altered smooth muscle tone are all important.

An excellent review from human medicine can be found here:

http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/126/8/975

A critical quote from this article is:

‘ It is noteworthy that overt right heart failure due to reactive PH rarely coexists with pulmonary edema, presumably because pulmonary vascular alterations that develop in the former scenario protect the lungs against alveolar and interstitial fluid transudation.’

That’s not necessarily to say that the same is true of cats and dogs generally but it would certainly fit with the situation in the present case.

I am going to take a good look at the next few DMVD dogs which I see with PAH. The progressive natural history of these tends to be:

1: initially signs of L CHF demand therapy

2: Signs of L CHF are controlled and therapy is titrated to effect.

3: At a later date deterioration (coughing, tachypnoea, increased respiratory effort) prompts further work up and PAH is diagnosed.

4: some patients progress to overt R CHF with ascites

Up to now I have usually assumed that situation 3 reflected deterioration in both L and R CHF. But many of the clinical signs are common to both PAH and L CHF. I now wonder how many of these dogs actually had pulmonary oedema at that stage.

From a therapeutic point of view this is a whole can of worms. R CHF is potentially much more than just a nuisance accumulation of ascitic fluid. Dysfunction of many organ systems might result (gut, kidneys, liver…). It may not be a coincidence that, in dogs, cardiorenal syndrome is usually seen in the setting of group 2 PAH with overt R CHF. We have the beginnings of some options for managing PAH (e.g. sildenafil) but, as yet, little evidence on which to base decisions such as when to start, which doses to use and so forth.

I love the way you bring logic into the interpretation. You have a sharp mind that is well ahead of the curve. Your deep passion for ultrasonography is duly noted. Keep up the excellent work and challenging thoughts . Bob Hylands, Canada.

Thanks Bob, appreciate the feedback