Possible tricuspid valve infective endocarditis in a Springer Spaniel

Infective endocarditis is a challenge both diagnostically and therapeutically. Because the heart valves are not readily accessible for sampling and clinical signs/clinical pathology are highly variable, many of the cases which form the published literature on the subject were confirmed post mortem. Many of those reported in the largest case series by Sykes et al. fall into this group.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16740075

I believe that this skews the impression we have of the disease towards it carrying a very high mortality rate. Almost by definition, milder cases with fewer complications and which go on to survive do not fulfill the criteria (‘modified Duke criteria’ based on human scoring systems) which would allow them to be regarded as confirmed or even probable.

Harvey is a case in point. He presented with a several week history of pyrexia, malaise and then rapidly deteriorating tachypnoea/hyperpnoea. No murmur had previously been noted. Routine haematology & biochemistry were non-specific

His thoracic radiographs are interesting in that, although he has unremarkable lung fields and cardiac silhouette in right lateral and dorso-ventral views, the left cranial lobe pulmonary vessels appear to be under-filled. On left lateral view the cardiac silhouette is dramatically different -which I can only imagine is due to redistribution of a small pericardial effusion (any opinions on this welcome! The presence of an effusion was later confirmed ultrasonographically).

Abdominal ultrasonography proved unremarkable.

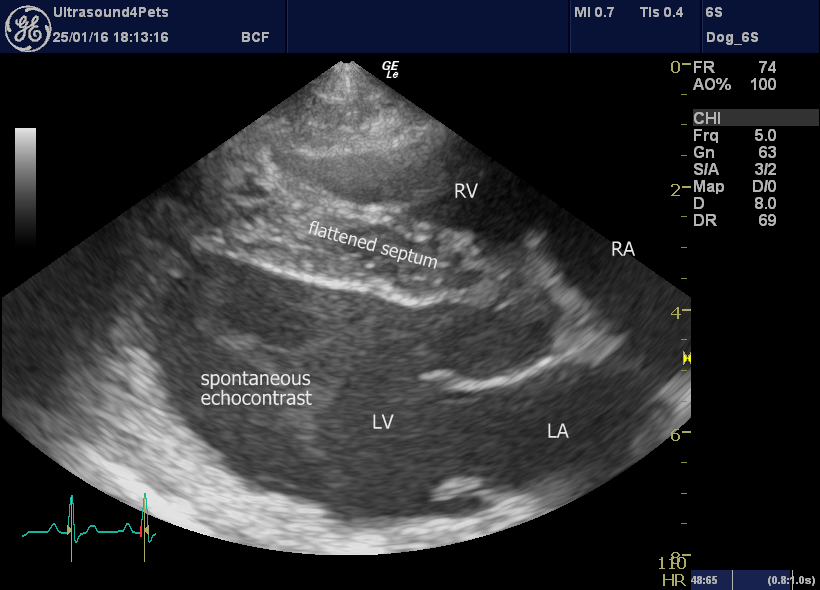

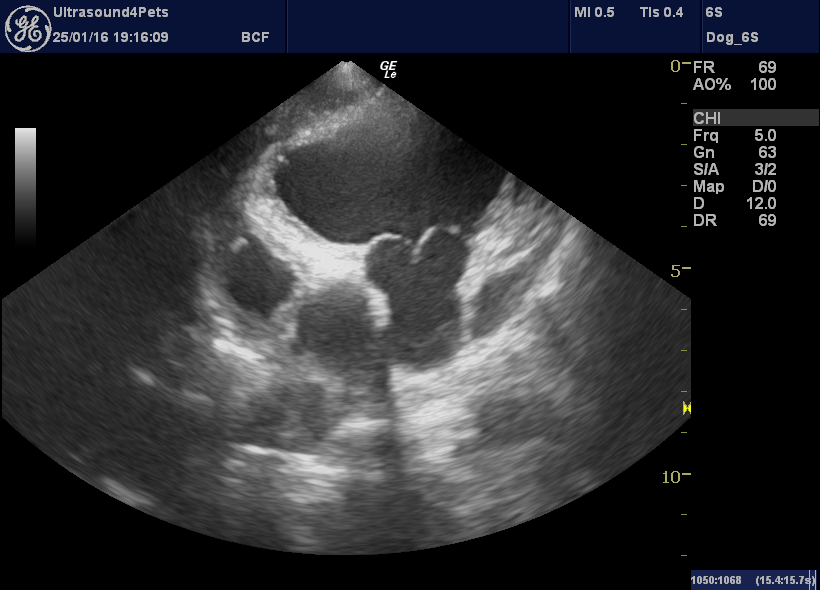

It’s when we come to the echocardiography that things get interesting. The right long-axis four-chamber view, as always, provides a good overview of cardiac haemodynamics. Here we see a proportionally small left heart (implying reduced pulmonary venous return and also suggesting that left heart CHF is unlikely to be the cause of respiratory signs) and a subjectively large right ventricle with systolic ‘flattening’ of the ventricular septum towards the left (implies increased resistance to RV outflow).

R long axis four chamber view

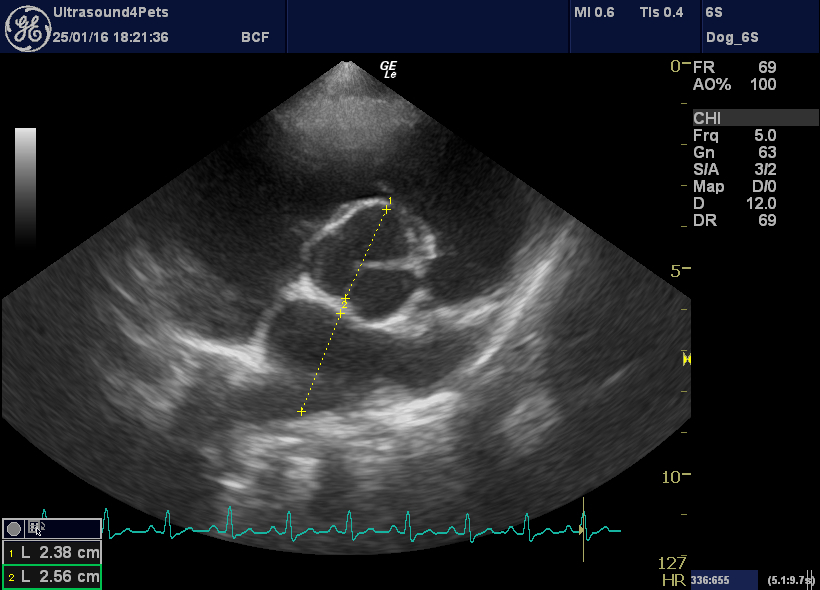

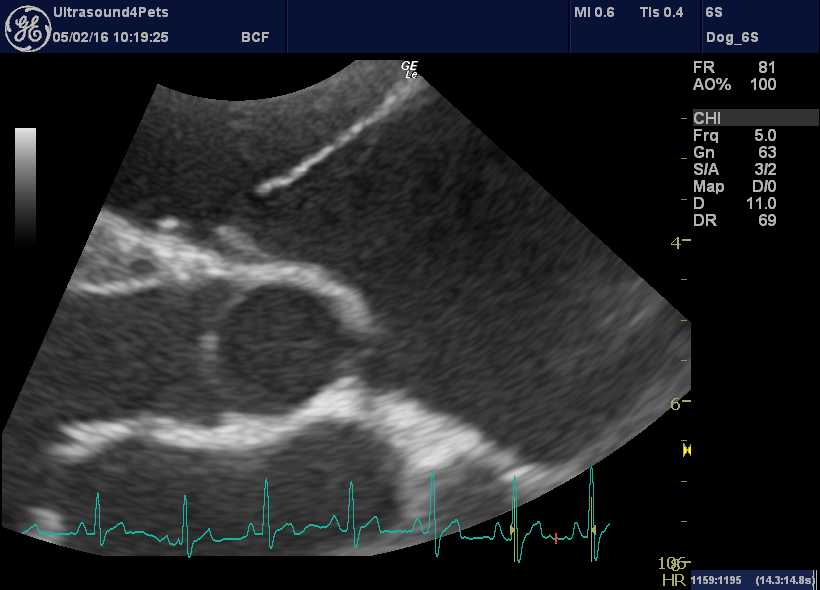

R transverse plane view at the level of the aortic valve. The left atrium appears under-filled -certainly not suggestive of L CHF

However, on inspection of the pulmonic valve and interrogation of main pulmonary artery flow there is no evidence of stenosis. Instead we have diastolic billowing of the pulmonic valve leaflets back towards the RV, a dilated main pulmonary artery (aortic diameter:PA diameter 1.3:1) and an asymmetrical PA flow pattern with a steep acceleration (low acceleration time:deceleration time ratio).

left cranial transverse plane view of the pulmonic valve showing diastolic ‘billowing’ towards the RV

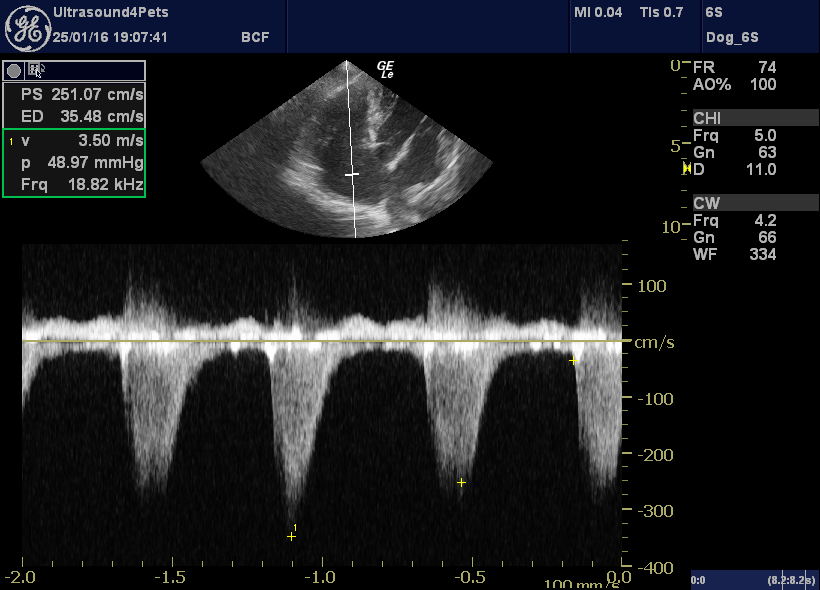

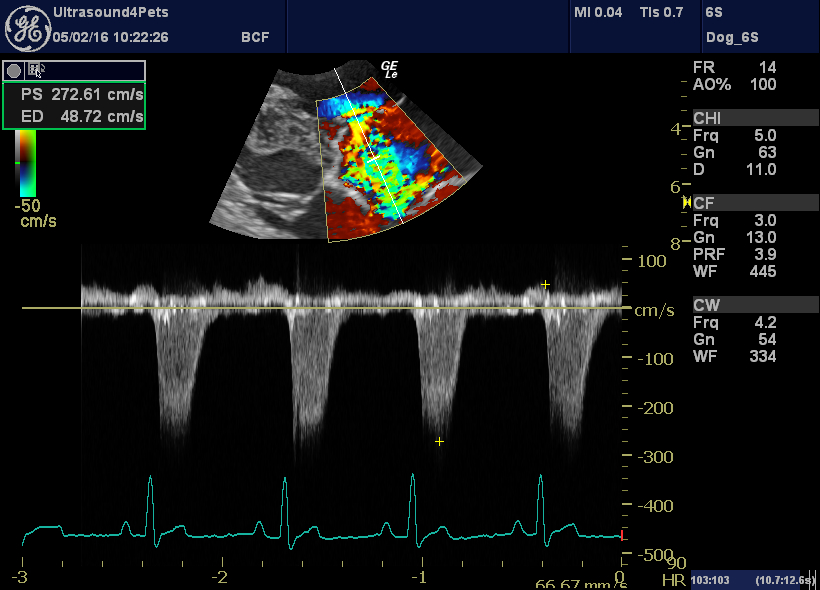

More objectively, there is a large eccentric jet of tricuspid regurgitation with peak flow velocity of 3.5 m/s. Even with normal RA pressure this suggests a systolic RV and PA pressure >50 mmHg (where normal is <30).

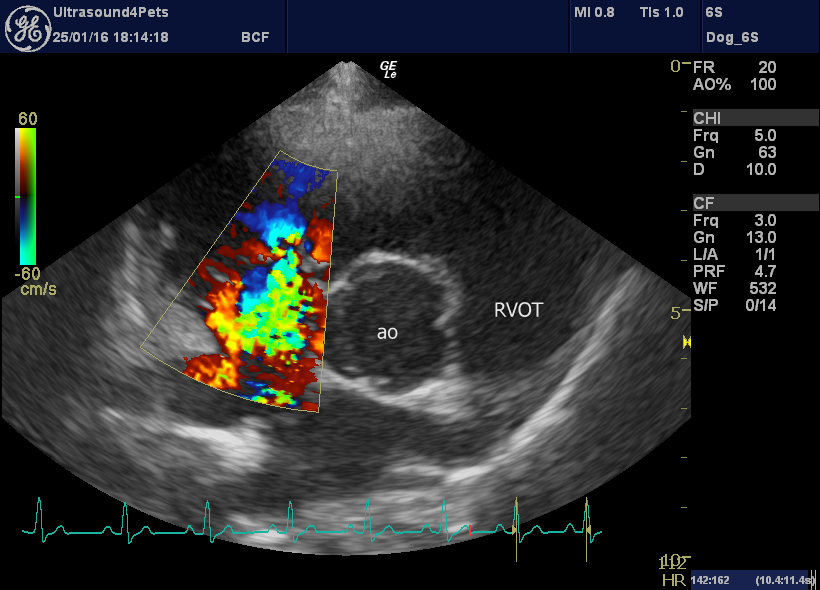

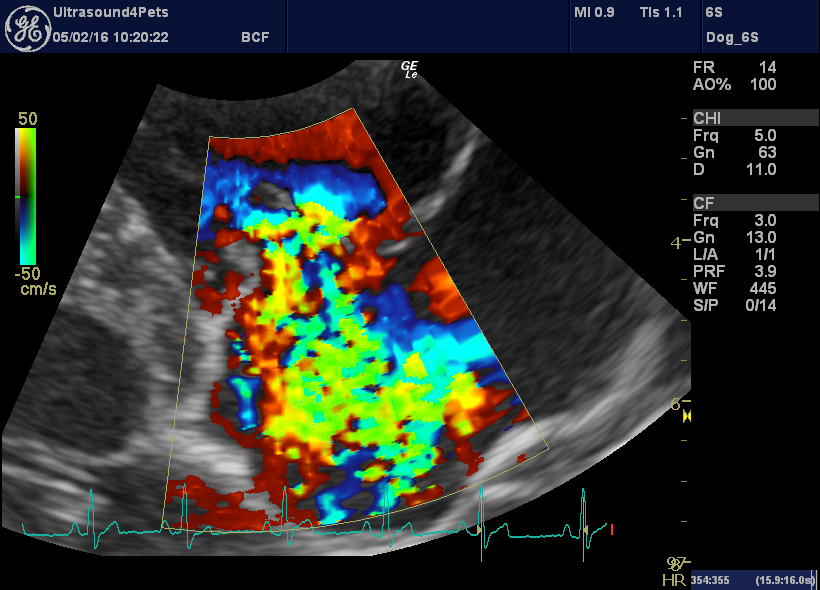

R transverse plane view showing tricuspid regurgitation jet

left apical view optimised for the tricuspid valve with CW interrogation of the tricuspid regurgitation jet

These phenomena all suggest the possibility of pulmonary hypertension: potential causes for which include primary lung disease and pulmonary thromboembolism. Ultrasonography of the lung fields revealed no obvious pathology.

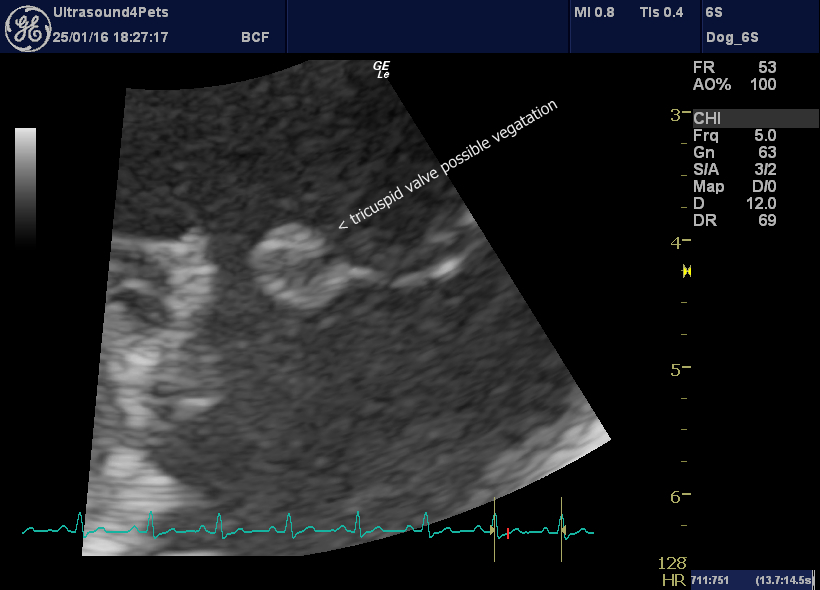

Details of the tricuspid valve are also interesting. The septal leaflet apears to be ‘tethered’ to the septum by short chordae tendinae and does not move freely. This is the characteristic appearance of congenital tricuspid dysplasia in many affected dogs.

However, in Harvey’s case. there are also oscillating vegetations near the tips of the valve leaflets.

R long axis oblique view of tricuspid valve leaflets: the septal one (left) is tethered, the parietal one (right) has a large irregularity at the tip.

Now, valve irregularities in dogs need to be interpreted with a healthy scepticism since 99+% of them are not due to infective endocarditis and right heart endocarditis is even less common. However, it raises the possibility.

A further finding, unusual in dogs, is spontaneous echocontrast in the left ventricle. This can be somewhat machine-dependent. However, in my experience the commonest pathologic causes are immune-mediated hemolytic anaemia and infective endocarditis – which appear to have marked effects on blood cell aggregation. More circumstantial evidence.

By the time of this echocardiogram, Harvey had been on intravenous antibiotics for >24 hours, and in view of an exponentially-increasing bill blood cultures were not performed. We elected to go with the antibiotics plus clopidogrel and monitor response.

In the event, he responded admirably. After a week of combined intravenous marbofloxacin and co-amoxyclav he was back to near normal. Treatment was continued with the same combo in oral form and by the time of a repeat echo two weeks later all evidence of both pulmonary hypertension and tricuspid lesions had fully resolved. At the time of writing, 6 weeks down the line he remains well and is off all treatment.

Tipped R long axis view post-treatment: there is still a large jet of tricuspid regurgitation

However, the parietal tricuspid valve leaflet now looks great!

…and the tricuspid regurgitation velocity is back to normal (implying that pulmonary hypertension has resolved)

Harvey, feeling better!

It would take several pages to discuss and debate all possible alternative causes of pyrexia. Pneumonia or other severe infections such as leptospirosis (sometimes associated with pneumonitis) are potential causes of antibiotic-responsive pyrexia with pulmonary hypertension. However, I believe that circumstantial evidence (especially antibiotic-responsive valve vegetations) supports a hypothesis of predisposing tricuspid dysplasia, then infective endocarditis and subsequent pulmonary thromboembolism.

The only other dog which I have seen with a reasonably convincing claim to right-heart endocarditis (involving a resolving mural RA vegetation) also survived long term.