Portosystemic shunts : to operate or not to operate?

It does sometimes feel as though shunt-ology could be a discipline in its own right: they seem to occupy an enormous part of our time and just when you think you know everything there is to know about shunts there’s another layer of complexity around the corner. A fundamental and thorny issue is the matter of when to recommend surgery.

The truth is that hard evidence has been surprisingly hard to come by. Or more specifically it’s difficult to compare results from differing data sets. Those which fail to respond well to medical treatment are obviously more likely to go to surgery and so forth. But what about those which do respond to medical treatment: are they likely to do better long term with surgery too?

Greenhalgh and others addressed the issue of medical v surgical treatment generally:

Greenhalgh SN, Reeve JA, Johnstone T, Goodfellow MR, Dunning MD, O’Neill EJ, Hall EJ, Watson PJ, Jeffery ND.

J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2014 Sep 1;245(5):527-33

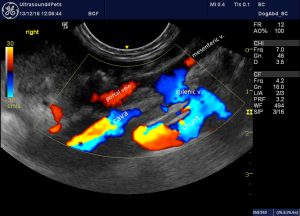

The crux of their findings is encapsulated in the Kaplan-Meier curves:

That looks pretty clear cut doesn’t it?

The main caveats are 1) there were only 27 dogs medically-treated and 2) patients were assigned to either medical or surgical treatment by owner choice after discussion and may have been biased by a variety of factors. Actually, I would have expected that the clinically less severe cases would be more likely to end up with medical treatment -which would tend to improve survival amongst this cohort.

Next up….

Center SA, Randolph J, Warner K, et al.

Long-term survival of dogs (n = 597) with congenital or acquired portosystemic shunting:1980–2010.

J Vet Intern Med 2012;26:781A ACVIM Forum 2012, New Orleans, LA (abstract)

This is a bigger study with 212 dogs medically-treated. On the face of it the patient population (referral hospital), the process of assignment to medical v surgical treatment, the nature of medical management (diet, lactulose, antibiotics) and the lack of data as to cause of death look similar to Greenhalgh’s study.

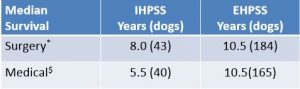

The results:

Great! We have one study reporting no difference in survival and one study reporting a profound difference.

Essentially, the figures for survival in operated dogs are very similar between the two studies. The difference lies in the success of medical management. It must be possible that the small number of cases in Greenhalgh’s study (only 21 dogs with extrahepatic shunts in the medical group) may have been a factor. However, it also seems worth looking at whether Center’s group were doing something different with their medically-treated group.

Whereas Greenhalgh’s dogs received ‘commercially available products for dogs with hepatic or gastrointestinal disease or homemade diets that contained controlled amounts of high-quality, easily digestible protein’, Center’s were fed ‘diets with restricted or modified protein’. So, probably fairly similar in this regard.

Greenhalgh’s received non-specified antimicrobials. Those amongst Center’s which received an antimicrobial got metronidazole.

Lactulose was also widely used in both series.

The medical management of hepatic encephalopathy (HE) is an interesting subject and much more open to debate than is reflected in the veterinary literature. A good review of human HE management can be found here:

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/186101-overview#a7

The important points being:

- protein restriction probably doesn’t improve HE in most patients and protein malnutrition can be an important cause of morbidity in itself.

- lactulose appears to be useful in preventing HE but care must be taken not to overdose as dehydration can precipitate HE!

- antibiotics appear to reduce the frequency of HE. The best evidence is for the use of rifamixin. As with all things relating to gut microbiota the situation is probably much more complex than simply ‘reducing numbers of bacteria’. Choice of antibiotic may be important in determining the composition and metabolic activity of gut flora. Rifamixin is consiered the drug of choice in people because of reduced adverse effects compared to alternative antibiotics. Metronidazole, for example, is associated with undesirable neurological and gastrointestinal sequelae.

This is interesting because we have some information on the use of rifamixin in dogs:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5053129/

…and it appears to be a safe option which might be worth investigating.

A further digression is recent work on the role of inflammation in HE and the potential for managing it with anti-inflammatories (e.g. NSAIDs).

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hep.21734/abstract

This would also appear to be an avenue worth investigating for canine and feline patients with problematic HE where surgery is not an option.

To return to the original crunch question of surgery v medical treatment of shunts we clearly don’t yet have a definitive answer but my conclusions in summary:

- patients with HE which fail to respond well to medical management should go to surgery if possible

- if surgery is not an option then oral lactulose, rifamixin and NSAIDs may be worth trying

- patients with minimal HE signs after medical treatment need a careful risk v benefit analysis.

On the risk side most surgeons report peri-operative mortality around 5-10%. This may improve with the use of prophylactic levetiracetam to reduce incidence of post-op seizures:

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1939-1676.2011.00819.x/abstract

…and the use of medetomidine CRIs to treat them:

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/vec.12431/abstract

On the benefit side, the important issue is the owner’s perception of the impact of the condition on the dog’s quality of life. This can be a very subjective matter.

In human medicine, where it’s obviously easier to gauge, ‘minimal hepatic encephalopathy’ has emerged as a previously-underestimated phenomenon with significant effects on quality of life (video-spatial orientation deficits, attention disorders, memory, reaction times, electroencephalogram slowing, prolongation of latency evoked cognitive potentials and reduction in the critical flicker frequency).

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30622374

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22728384

We just don’t know how much of an issue this is in dogs: although I suspect it may be significant. Personality often changes appreciably after successful shunt attenuation.

I tend to think that outcomes seen with non-surgical management in the study of Greenhalgh et al. may be more negative than is generally the case. Center’s study is much bigger and fits better with what we see in practice: quite a lot of middle-aged to old dogs coping well with shunts. There may be factors in medical management which we don’t yet fully understand which account for differences in survival figures and could potentially be exploited in the future. We should probably think more carefully about diets and antibiotic choice.