Feline ureteral calculi

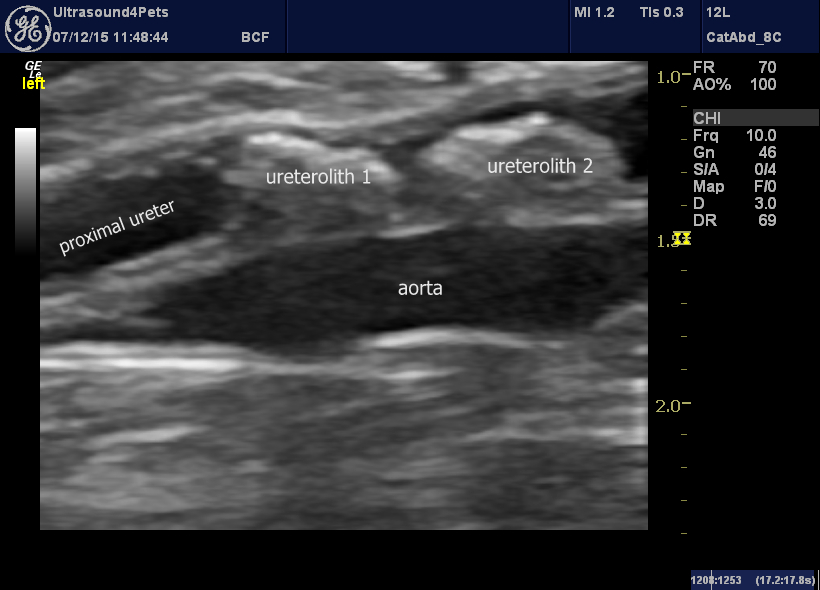

Since the first published description of feline ureteral calculi in 1991 we’ve reached the point where it has been described as the commonest cause of azotaemia in cats. If you prospectively scan a lot of azotaemic or non-specifically poorly cats a significant proportion will have ureteral calculi.

Typical acute cases are poorly cats with abdominal pain, malaise and vomiting. Azotaemia is variable depending on the status of the contralateral kidney. Many of these patients have serial episodes of ureteral obstruction. Most of these calculi do eventually pass and, depending on how long that takes, the affected kidney is left with a variable degree of permanent impairment. During these early episodes, if one kidney has good function then azotaemia may not be apparent. Later, if one kidney is already impaired, when the second one obstructs then azotaemia develops. This often manifests as a small-kidney, big-kidney scenario. The small one being previously affected and the large one acutely so.

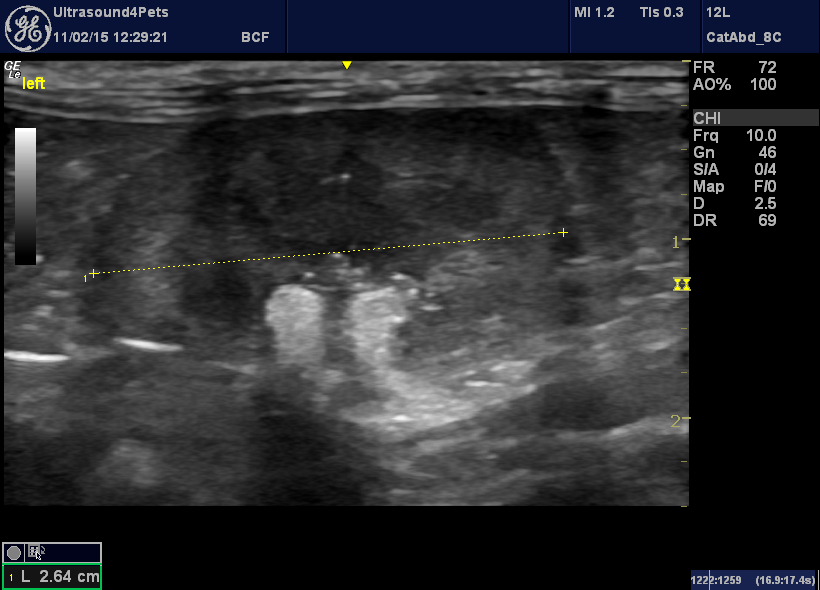

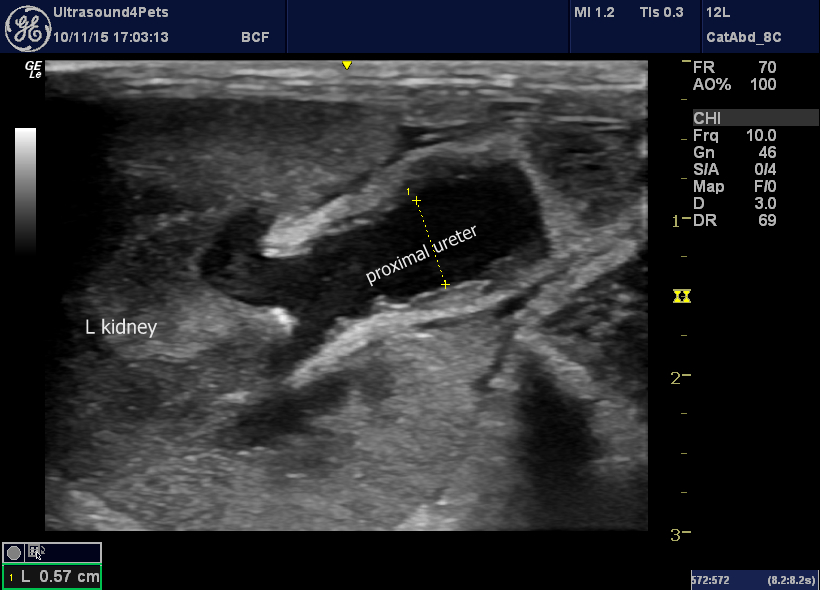

Frontal plane view of the left kidney of an azotaemic cat. This is a small kidney with mineralisation around the pelvis. I would hypothesize that this kidney suffered an earlier episode of ureteral obstruction during which some permanent impairment occurred despite the eventual passing of the ureterolith.

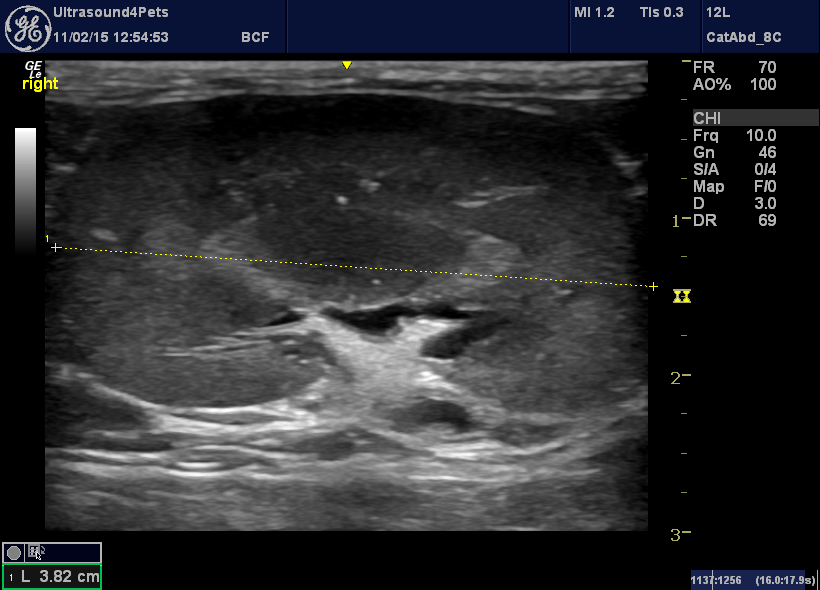

The contralateral (right) kidney from the same cat. It is within normal limits of length. The renal pelvis is not appreciably dilated despite ureteral obstruction.

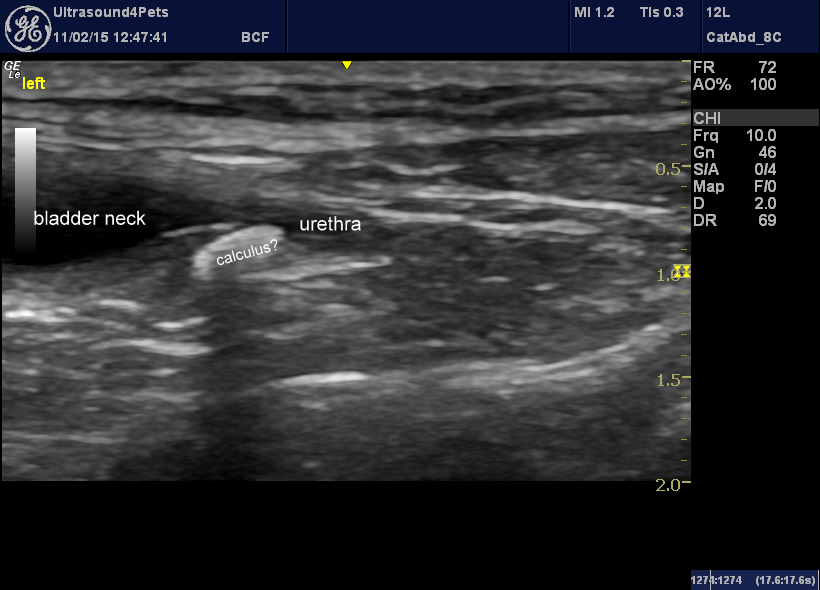

sagittal plane view of the bladder neck. There is a ureteral calculus sitting in the terminal part of the right ureter.

Acutely presenting ureteral calculi are a therapeutic dilema. Many of them may wash out with diuresis but, after a few days, the risk of permanent renal damage rises. Whilst ureterotomy is an option it is associated with a relatively high incidence of complications (urine leakage, stricture). Some of these cats have multiple calculi and/or will suffer repeated bouts of obstruction. Stenting is almost certainly better where available.

Hydronephrosis occurs where a ureteral calculus does not spontaneously pass and becomes chronic:

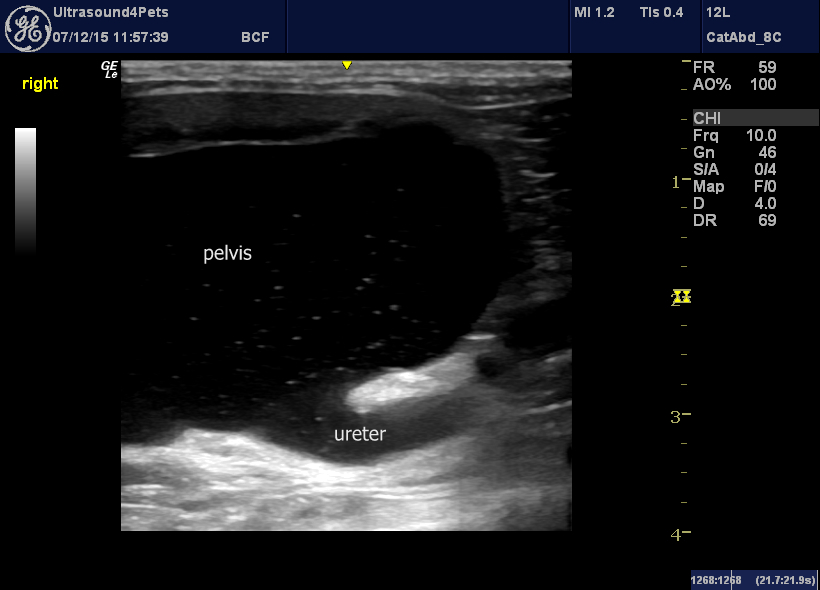

Hydronephrosis resulting from chronic ureteral obstruction

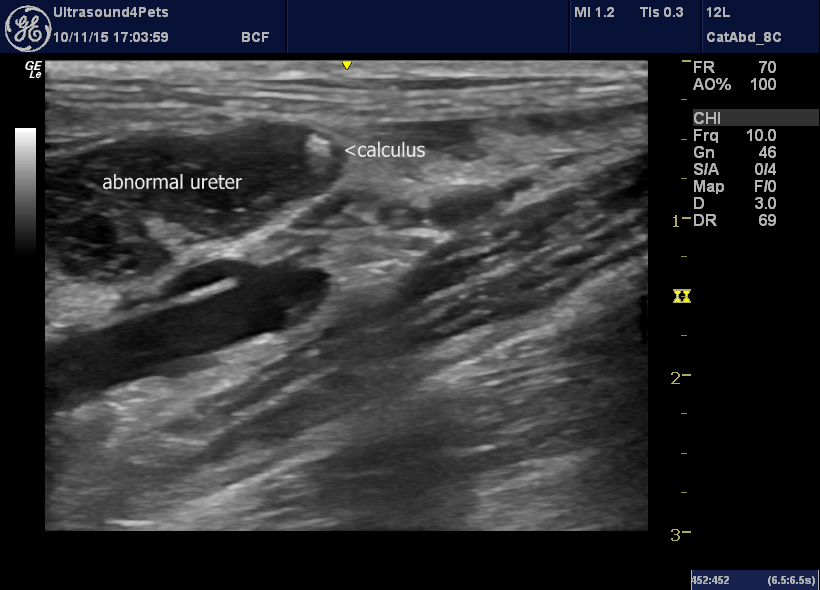

The obstructed ureter from the same cat

I believe that, in human medicine, uretero-nephrectomy would be the usual course of action. Some animals undoubtedly cope without surgery. However, it is difficult to be sure that they are not painful and there is a risk of pyelonephritis:

Transverse plane view of a chronically-obstructed feline kidney with grumbling pyelonephritis: the ureteral wall is thickened and hyperechoic. There was also a small retroperitoneal effusion.

The obstructing calculus from the same cat. Urine above the obstruction is clearly turbid.