Canine infective endocarditis: observations on presentation, incidence and sonography

There remain relatively few published case series of infective endocarditis in dogs. The largest being Sykes et al. published in two parts:

J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2006 Jun 1;228(11):1723-34.

Evaluation of the relationship between causative organisms and clinical characteristics of infective endocarditis in dogs: 71 cases (1992-2005).

Sykes JE1, Kittleson MD, Pesavento PA, Byrne BA, MacDonald KA, Chomel BB.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16740074

J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2006 Jun 1;228(11):1735-47.

Clinicopathologic findings and outcome in dogs with infective endocarditis: 71 cases (1992-2005).

Sykes JE1, Kittleson MD, Chomel BB, Macdonald KA, Pesavento PA.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16740075

These articles documented for the first time the phenomenal variability of presentation in IE.

- Lethargy 61% of cases

- Inappetence 57%

- Locomotor problems 53%

- Vomiting 27%

- Respiratory difficulty 20%

- Weight loss 13%

- Coughing 13%

- Ocular discharge 10%

- Neurological signs 6%

Others included collapse, diarrhoea, epistaxis, PUPD, hypersalivation, nasal discharge and oral ulceration.

Physical findings at initial presentation:

- murmur 59%

- tachycardia 50%

- Arrhythmia 19%

- Fever 38%

- (7% had no murmur and no fever)

- neurological signs 23% (ataxia, anisocoria, strabismus, vestibular signs)

Amongst a plethora of other findings were icterus, hyphaemia, abdominal enlargement, petechiae, oral and cutaneous ulcers.

This is a bit of a departure from the picture painted in lectures (as far as I can remember…maybe I wasn’t concentrating) when I was at vet school of dogs with shifting lameness, fever and new murmur. I’m coming round to the view that a prospective approach with echocardiography and abdominal ultrasound to large breed dogs with serious illness of various kinds is always likely to yield a scatter of endocarditis cases amongst them. Abdominal findings of specific interest as regards IE include splenic or renal infarcts and arterial thromboemboli.

Anisocoria and cranial nerve deficits resulting in tongue protrusion in a GSD cross with infective endocarditis.

An oblique view of the septal mitral valve leaflet from the same dog: there is a plausible vegetation on the atrial aspect of the valve.

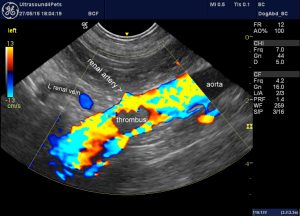

abdominal aorta of the same patient: there is a large thrombus in the region of the origin of the renal arteries.

Apparent renal infarction resulting from thromboembolism.

Splenic infarcts in another canine IE case

My impression is that the commonest locomotor presentation is of a hunched attitude with pain and unwillingness to walk. It’s often difficult to localise the pain but presumably thromboembolic disease and polyarthritis are involved.

A hunched position with hard-to-localise pain is quite a common presentation. This is the patient whose echocardiography is shown above.

Another IE patient with ‘back end pain’

It’s interesting to note the very recent publication of evidence for the existence of Bartonella-associated IE in Europe.

Polymerase chain reaction detection of Bartonella spp. in dogs from Spain with blood culture-negative infectious endocarditis.

Roura X, Santamarina G, Tabar MD, Francino O, Altet L.

J Vet Cardiol. 2018 Aug;20(4):267-275. doi: 10.1016/j.jvc.2018.04.006. Epub 2018 May 25.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29807750

We’ve known for the last 20 years or so that Bartonella Vinsonii is an important agent of IE in the western US. In the Spanish study polymerase chain reaction was positive for eight out of 30 dogs included (26.6%). Bartonella rochalimae, Bartonella vinsonii subsp. berkhoffii, and Bartonella koehlerae were detected in valve tissue or blood

My understanding is that we don’t really know which arthropod parasites are responsible for transmission to dogs or which reservoir species might be involved. That being the case it’s difficult to predict whether Bartonella-associated IE might be a potential issue in the UK. It may be worth testing culture-negative IE cases.

It appears that both co-amoxyclav and fluoroquinolones are likely effective against Bartonella which is encouraging since this combination our default empirical treatment for IE at VPS.