Lung ultrasound in small animals: late 2021 update

As I might have said before, lung ultrasound is the gift that keeps on giving. In the beginning lung ultrasound wasn’t even a thing; then it became all the rage and we recognised some fundamental patterns. With time we’ve worked out some more subtleties and developed new understanding of concepts that we previously thought we understood. The learning curve remains quite steep: I have a feeling that there’s plenty more refinements to follow. This blog post aims to include a few interesting cases to illustrate some things that I’ve learned recently.

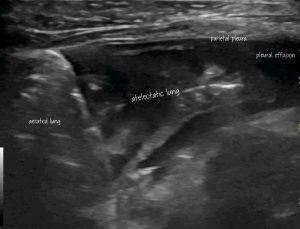

For starters I’d like to claim the term ‘Anteater sign’ to describe the appearance of compressive atelectasis in the peripheral lung in animals with pleural effusion (of any cause).

In my experience this isn’t always recognised as such by occasional sonographers. In contrast to pneumonic lung the interface between aerated lung and consolidated lung is less irregular and less likely to feature intense B lines.

Transthoracic para-dorsal plane view with the probe aligned with the intercostal space. Aerated lung to the left of image contrasts with hypoechoic atelectatic lung to the right

Strictly-speaking, one has to be cautious about assigning this peripheral consolidation purely to compressive atelectasis. Since, usually, we don’t know that it looked normal before the effusion arose.

This particular feline patient is a case in point since further examination reveals a heart base mass which might be infiltrating the abnormal lung.

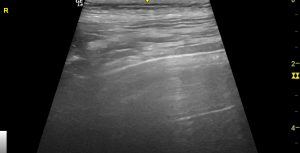

Next up, interstitial lung disease. I’ve seen many dogs over the years with presumed interstitial fibrosis (some of them also underwent lung CT and other investigations) and noted considerable variation in the appearance. As time has gone on, I’ve realised the importance of critical examination of the pleural line.

This elderly West Highland White Terrier, in whose care I was involved for several years, would be typical. He developed progressive pleural line changes along with B lines and coalescing B lines (‘white lung’ or ‘glass rockets’).

In this still image…

Transthoracic lung ultrasound: canine IPF. Although I don’t have proof, it seems logical to me that the thick hypoechoic band represents the abnormal visceral pleura and consolidated lung immediately beneath it. The white line superficial to that represents the interface between parietal and visceral pleura. The hyperechoic white line below it is the interface between visceral pleura/consolidated peripheral lung and aerated lung.

The thickening of the hypoechoic pleural line is obvious (compare to normal below).

Transthoracic lung ultrasound: normal canine pleura and lung A lines

Pleural changes represent the best way of distinguishing interstitial fibrosis from interstitial oedema in lung with B lines.

These issues are addressed in respect of human medicine by Volpicelli:

Chest. 2020 Oct; 158(4): 1323–1324.

Lung Ultrasound B-Lines in Interstitial Lung Disease Moving From Diagnosis to Prognostic Stratification

Giovanni Volpicelli

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7533744/

‘Pleural line alterations are usually present in pulmonary fibrosis and are one of the features that can be useful in differentiating cardiogenic from noncardiogenic B-lines‘

‘Irregularities of the pleural line do not correspond to alteration of the anatomic pleura that is not involved in the disease. Rather, the sonographic image of an irregular pleural line is the effect of the subpleural interstitial alterations with decrease of aeration in the lung periphery. Although one may observe a perfectly regular pleural line with multiple B-lines in the early phase of the disease, the irregularity of the pleural line is always and for definition accompanied by B-lines. For this reason, the morphologic description of the sonographic image of the pleural line may be redundant information once the diagnosis has been done. B-lines remain the main critical signs to diagnose and prognosticate interstitial lung disease‘

The issue of nomenclature for lines seen on lung ultrasound is also worth revisiting; since this area has clarified with time….as summarised by Lee e al.

Med Ultrason 2018, Vol. 20, no. 3, 379-384

A common misunderstanding in lung ultrasound: the comet tail artefact

Francis Chun Yue Lee, Christian Jenssen, Christoph F Dietrich

https://sjrhem.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/1573-8467-1-PB.pdf

‘Of the many artefacts described in the lung ultrasound (LUS) literature, the most often talked about and perhaps creating the most confusion amongst practitioners is the comet tail artefact (CTA) or ‘lung comets’. CTA is so named primarily due to their appearance on US but it now known that many disparate linear vertical artefacts share this morphology‘

‘Despite the superficial resemblance, CTA and ring down artefact (RDA) differ in respect of genesis, morphology and differing clinical significance in LUS‘

Generally-speaking, B lines (which are a form of ring-down artefact) are characterised by their intensity and the fact that intensity persists down to the bottom of the screen. CTAs fade deeper in tissue.

RDAs are generated by sound propogated between tightly packed air-bubbles in fluid. CTAs arise through reverberation at interfaces.

As the authors of this recent paper explain, the literature of lung ultrasound is fairly riddled with confusion on this matter.

Daniel Liechtenstein, who was one of the founders of lung ultrasound, likes to refer to scattered, increased B lines as ‘septal rockets’ since they arise in thickened subpleural interlobular septae and coalescing B lines (‘white lung’) as ‘glass rockets’ since this correlates with ground glass opacity on lung CT.

Chest 2019 Jul;156(1):21-25.

Current Misconceptions in Lung Ultrasound: A Short Guide for Experts

Daniel A Lichtenstein

https://journal.chestnet.org/article/S0012-3692%2819%2930615-4/fulltext

I think I prefer ‘white lung’.

Anyway, with reference to the images of the IPF patient above. Normal A lines are obscured. In my experience this is a common feature of IPF in dogs. Often the lung just looks ‘white’ (in reality some shade of pale grey!), distinct, individual B lines may not be obvious. This looks like ‘ground glass’ on ultrasound as well as on CT.

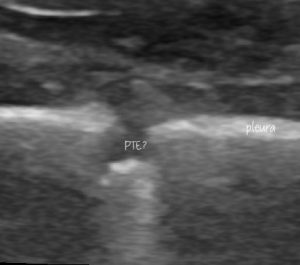

Finally, I want to talk about pulmonary thromboembolism (PTE): a subject not much addressed in small animal sonography texts.

The first thing to say is that a patient with severe PTE may have no visible abnormalities on transthoracic lung ultrasound.

This poor Newfoundland with IMHA has a huge thrombus almost occluding the right main pulmonary artery

..and yet a thorough examination of the right lung shows no abnormality

Other cases I’ve seen with putative PTE have had irregular subpleural consolidations. These are usually quite small, often wedge-shaped and lack the surrounding B lines characteristic of acute pneumonias.

The following patient was a dog with PLE-induced hypoalbuminaemia, a large RV thrombus and acute tachypnoea.

Some better, still images of those lung lesions:

This looks pretty compatible with what’s described in the human literature:

http://www.emdocs.net/ultrasound-g-e-l-multiorgan-ultrasound-for-pulmonary-embolism/

The latter gives some idea of how reliable lung ultrasound might be for PTE:

‘The sensitivities, specificities and diagnostic accuracies of lung ultrasound vs. CT findings were 88.2%, 87.5% and 93.5% for pneumonia, 71.4%, 80.9% and 87.1% for pulmonary embolism, respectively‘

Essentially, not bad.