Ultrasound in the diagnosis of acute enterocolitis in dogs and cats

Almost the most frequent presenting problem we see in our sonography practice is canine acute abdomen. And perhaps, more specifically, acute vomiting which fails to resolve within a couple of days supportive care. The bottom line for these is ‘does this dog need surgery or will it resolve with supportive care’. If you can see an obstruction (intussusception, foreign body, mass lesion, colonic torsion or whatever) then that question can be answered relatively easily. My impression would be that experienced sonographers are good at identifying obstructions; and that is also borne out by the published data.

Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2011 May-Jun;52(3):248-55. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8261.2010.01791.x. Epub 2010 Dec 28.

Comparison of radiography and ultrasonography for diagnosing small-intestinal mechanical obstruction in vomiting dogs.

Sharma A1, Thompson MS, Scrivani PV, Dykes NL, Yeager AE, Freer SR, Erb HN.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21554473

In that paper ultrasound had a 97% rate of definitive diagnosis for obstruction (compared to 70% for radiography).

What’s more complicated is the situation where an obstruction is not apparent. It’s possible to spend a lot of time trying to ‘prove a negative’ and always leaves a slightly unsatisfactory uneasiness until the patient recovers. So, what features can be used to positively identify acute gastro-entero-colitis?

For a very common problem there is relatively little published on the matter.

Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2010 Jan-Feb;51(1):69-74.

Ultrasonographic appearance of canine parvoviral enteritis in puppies.

Stander N1, Wagner WM, Goddard A, Kirberger RM.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20166398

Findings included ‘ fluid-filled small intestines in 92.5% of subjects, and stomach and colon in 80% and 62.5% of subjects, respectively. Generalized atony was present in 30 subjects and weak peristaltic contractions indicative of functional ileus observed in the remaining 10 subjects. The duodenal and jejunal mucosal layer thicknesses were significantly reduced when compared with normal puppies with mean duodenal mucosal layer measuring 1.7 mm and jejunal mucosal layer 1.0 mm. Additionally, a mucosal layer with diffuse hyperechoic speckles was seen in the duodenum (15% of subjects) and the jejunum (50% of subjects). The luminal surface of the duodenal mucosa was irregular in 22.5% of subjects and the jejunal mucosa in 42.5% of subjects. In all of these subjects, changes were accompanied by generalized indistinct wall layering. Small intestinal corrugations were seen within the duodenum in 35% of subjects and within the jejunum in 7.5%‘

That’s a good start and I would think that most of those observations hold true for adult dogs with acute non-specific vomiting and diarrhoea.

Diarrhoea can certainly be a feature in some dogs with GI obstruction. However, they rarely have large volumes of liquid faeces in the colon in the same way as dogs with entero-colitis.

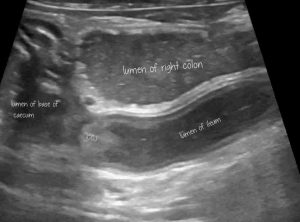

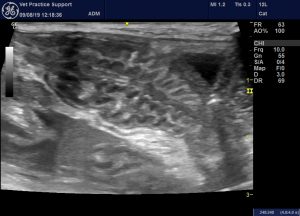

Longitudinal plane view of the caudal abdomen showing a dilated, fluid-filled loop of gut

It’s important to be able to distinguish between fluid-filled colon and fluid-filled small intestine. That is not always straightforward. Whilst, in healthy dogs, it’s usually easy enough to tell thin-walled large bowel from thick-walled small intestine, the wall of distended, obstructed small intestine can have thickness which overlaps with the thickness of colonic wall. And, conversely, thickened colon wall in colitis can look like small intestine. Happily the identity of colon can usually be confirmed by following the distended section caudally into the pelvic canal (as in the image above: the bladder is top right of image) or cranially and to the right into the ileocecocolic junction.

Frozen frame from the preceding video: this is a longitudinal plane view with cranial to the left of picture. The ileum enters the ICCJ from caudal.

The ICCJ is easier to identify in dogs with enteritis because the caecum and colon tend to be relatively empty or contain liquid diarrhoea which obscures the incoming ileum less than normal faecal matter. It can consistently be found deep to the descending duodenum on the right side of the mid-abdomen.

Once the colon is confidently identified, abnormal appearance of the large intestinal wall is a further strong positive predictor of colitis. Obviously the colon wall in small intestinal obstruction is usually unremarkable.

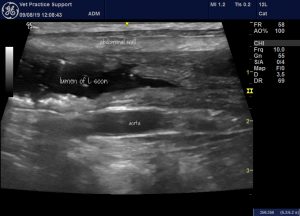

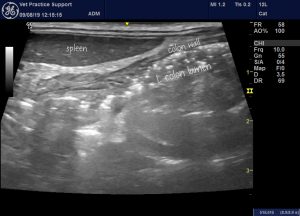

Typical appearance of the colon in colitis. The wall is diffusely and evenly thickened with gas bubbles adhering to the mucosa.

A longitudinal plane view from the left flank showing the colon of another dog with acute enterocolitis. Again the colonic content is liquid with gas bubbles. The wall is diffusely thickened. Differentials for this appearance include acute colitis and pancreatitis. Diffuse colon wall thickening with gassy diarrhoea usually suggests that the case is not surgical.

In some cases the colon is half-filled with gas and half liquid diarrhoea: creating a linear interface artefact:

Visualisation of the ICCJ has a further benefit in that it allows positive identification of the ileum. In the first video clip above the appearance of the ICCJ area alone would make me confident that this dog does not need surgery. The ileum is visibly free from mechanical obstruction and yet has a persistently distended lumen. That makes it highly unlikely that there is small intestinal obstruction higher up the gut and also tells us that there is some degree of functional ileus…again strongly suggesting enteritis rather than obstruction.

The ileocaecocolic junction in another dog with acute enteritis. Although not much addressed in textbooks, the canine ICCJ is easy enough to find in most dogs with a bit of practice. Once found it allows definitive identification of the ileum and proximal large bowel. That’s important in establishing which parts of the gut are dilated or thickened.

The small intestinal wall is also frequently abnormal in enteritis cases. It’s variable and slightly subjective in many cases. Diffuse wall changes are much more likely to accompany a primary enteritis than, for example, an obstructing foreign body.

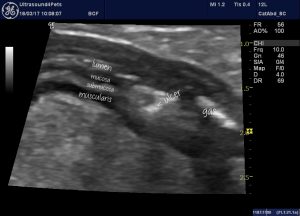

A loop of jejunum in a dog with severe acute enteritis. The lumen is abnormally dilated (particularly if this dilation does not resolve through peristalsis within a few seconds), The mucosa has areas with hyperechoic speckling and the supeficial luminal part of the mucosa is diffusely hyperechoic. The speckling is usually due to gas bubbles whch may also be seen in the gut content and coalescing into larger pockets of intraluminal gas in some loops: as seen at the right hand end of the section pictured.

Typically, dilated loops of small intestine in dogs with enteritis do not exceed 15mm serosa-serosa in dogs. A degree of dilation exceding this is not completely specific but should raise suspicion of mechanical obstruction. The cut off for cats is around 12mm.

A loop of jejunum from a dog with severe acute enteritis. The wall layering is indistinct in places and there are irregular areas of discontinuity in the mucosa which I take to be ulcers. This dog eventually recovered fully but took 3 weeks to do so.

Small intestinal corrugation suggests enteritis in the broadest sense: either primary or secondary to pancreatitis or septic peritonitis. Pronounced corrugation suggests that mechanical obstruction is probably less likely than acute enteritis.

Very similar changes in the duodenum of a cat with acute severe enteritis: the duodenal lumen contains an abnormal number of gas bubbles and the mucosal surface is subtly irregular.

The jejunum of the same cat. The lumen is diffusely, persistently, mildly dilated. The mucosa is diffusely hyperechoic.

The gut is probably the most challenging organ to assess sonographically. To be brutally honest, it’s also the area where there is the most difference between the diagnostic value gained by an experienced sonographer compared to a general practitioner with an ultrasound machine.